All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Metabolic Bioproducts of Soil Streptomycetes and Their Effect on RNAi-Mediated Resistance of Tomato Plants Against Root-Knot Nematode Meloidogyne Incognita

Abstract

Introduction

Streptomyces species are renowned for producing bioactive natural products, particularly those that induce plant resistance against pathogens and nematodes. This study aimed to investigate the ability of metabolic bioproducts from Streptomyces netropsis IMV Ac-5025, Streptomyces violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and Streptomyces avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 to affect RNAi-mediated resistance in tomato plants against the root-knot nematode.

Methods

Spectrodensitometric Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC), High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), and Gas Chromatography (GC) were used to identify natural products of streptomycetes. The resistance of tomato plants to Meloidogyne incognita was evaluated through artificial nematode inoculation coupled with phenological viability assessment. The extent of si/miRNA-driven gene silencing was determined via dot blot hybridization and inhibition of protein synthesis in a wheat germ cell-free translation system.

Results

Soil-derived Streptomyces strains were shown to produce diverse bioactive compounds, including antibiotics, lipids, phytohormones, and sterols, and novel bioproducts were developed based on their secondary metabolites (Phytovit, Violar, Averkom, and Averkom nova). Incorporation of these bioproducts into the nutrient medium significantly improved shoot regeneration rates in isolated plant explants. Dot blot hybridization and translational inhibition assays in a wheat germ cell-free system confirmed their phytoprotective effect via the RNA interference mechanism. In vitro cultivation of tomato plants supplemented with biotreatment resulted in a marked enhancement of resistance to M. incognita.

Discussion

The secondary metabolic complexes produced by Streptomyces strains promote plant growth and development while enhancing immunity and supporting the efficient operation of signaling networks involved in cellular responses to nematodes. Their activity is mediated through elicitor signals that trigger the de novo synthesis of plant si/miRNAs, which confer protection against M. incognita. These findings highlight the potential of these metabolites to advance eco-friendly strategies for controlling root-knot nematodes and to develop resistant plant lines.

Conclusion

Soil-streptomycete metabolites could be utilized in RNA interference to enhance tomato resistance to root-knot nematodes viade novo synthesis of protective small interfering and microRNAs, supporting agrobiological applications.

1. INTRODUCTION

Tomato plants (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) are one of the most widely cultivated horticultural crops worldwide, yet their productivity is severely constrained by phytopathogens and pests, causing significant yield losses in diverse agroecological settings. Conventional control strategies, including chemical nematicides, face limitations due to environmental concerns and reduced efficacy under changing climatic conditions. Consequently, sustainable approaches that enhance plant innate resistance are urgently needed [1, 2]. Harvest loss is now a major concern and is receiving considerable attention from scholars. The root-knot nematode M. incognita is among the most prevalent and destructive plant parasites, posing a serious threat to a wide range of vegetable crops. Beyond direct physiological damage to root systems, it exacerbates plant vulnerability by facilitating secondary infections with bacterial and fungal pathogens [3]. An eco-friendly alternative to this problem lies in biotechnological approaches. Actinobacteria of the genus Streptomyces have attracted considerable research interest due to their remarkable biosynthetic potential and their ability to suppress phytopathogens and plant-parasitic nematodes in the soil [4]. They have received significant attention in the context of general and industrial microbiology as effective antimicrobial agents with plant growth promotion properties [5]. The bioactivity of their metabolites encompasses inhibitory effects on pathogenic microorganisms, antiparasitic properties, and plant growth regulatory activity via phytohormones. Nematodes can be directly affected by streptomycetes through the action of nematicidal antibiotics, such as actinomycin and aureothin. Several species within this genus are recognized for their ability to produce nematicidal metabolites that are effective against juveniles of the Meloidogyne genus (S. cacaoi, S. rubrogriseus, S. antibioticus, and S. albogriseolus) [6]. However, the effect of antibiotics produced by Streptomyces species on plants goes beyond antagonism towards pathogens; they also play a crucial role in regulating plant protective systems. Modern approaches to plant protection are based on triggering their own resistance by using natural products that enhance the plants' own protective properties and stimulate their growth and development, ultimately resulting in a safe crop [7]. They also trigger a cascade of biochemical reactions within plants, extensively interacting with plant roots and enhancing resistance to both biotic stresses (such as insect herbivores and microbial pathogens) and abiotic stresses [8]. Recent advances in RNA interference have highlighted the possibility of employing microbial metabolites to trigger de novo synthesis of protective small interfering and microRNAs in plants. Such strategies may provide an innovative agrobiological solution to strengthen plants’ resistance against parasitic nematodes and reduce dependence on synthetic inputs [9, 10]. These small RNAs play a crucial role in gene silencing mechanisms, which help regulate stress responses and defense mechanisms, and can be induced by metabolites of beneficial soil bacteria. By targeting and degrading specific mRNA sequences of invading pathogens and nematodes, si/miRNA, aided by bacterial metabolites, effectively bolsters the plant's immune system and overall resilience [11]. In previous years, strains of S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025, S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 were isolated [12, 13]. They have high bioactivity and produce a wide range of secondary metabolites and metabolic bioproducts based on the enhanced growth of agricultural crops, boosted yield, and improved product quality [14]. The nematicidal activity of ethanolic extract of S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 was also reported [15].

The study of the biosynthetic potential of Streptomyces strains, producers of bioactive compounds, is crucial for understanding the mechanisms underlying their protective properties [16]. We hypothesize that natural metabolites of Streptomyces spp. can induce plant resistance against parasitic nematodes. The aim of the study is to explore soil Streptomyces strains as a source of metabolic bioproducts capable of strengthening RNAi-mediated resistance in tomato plants against root-knot nematodes, with potential applications in sustainable crop protection. This included characterization of the biosynthetic capacity of streptomycetes, with emphasis on their ability to simultaneously synthesize a range of bioactive compounds exhibiting both antagonistic and plant growth-regulating properties, to analyze the resistance of tomato plants against M. incognita, and to investigate the molecular-genetic characteristics of resistance in tomato plants through the de novo synthesis of siRNA and miRNA molecules and their silencing activity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cultivation of Streptomyces Strains and Obtaining of Metabolic Bioproducts

S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025, S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and S. avermitilis ІМV Ас-5015 were isolated by scientists at the D.K. Zabolotny Institute of Microbiology and Virology of the NAS of Ukraine and registered in the depository of non-pathogenic microorganisms at the Institute [13, 14]. These strains are also registered in the Ukrainian Collection of Microorganisms (UCM) under the following accession numbers: S. netropsis UCM Ac-2186, S. violaceus UCM Ac-2191, S. avermitilis UCM Ac-2179, and bioproducts based on their secondary metabolites were developed. Their cultivation was conducted in liquid nutrient media (synthetic and organic) as previously described in the literature [17, 18]. Ethanol (96%) was employed for the extraction of secondary metabolites and the development of bioproducts [17]. The resulting ethanolic biomass extracts were combined with culture liquid supernatants at a 1:2.5 ratio. Phytovit is a bioproduct based on metabolites of S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025. Violar consists of metabolites produced by S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027. Averkom is composed of S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 metabolites. Averkom nova is a modified version of Averkom, produced by adding 0.01 mM of chitosan. These bioproducts are standardized based on their antibiotic concentration [14, 15].

2.2. Determination of Antibiotics in the Ethanolic Biomass Extracts of Streptomycetes

To quantify the total content of avermectin, polyene, and anthracycline antibiotics in the biomass of streptomycetes, a modified extraction protocol [18] was applied using the polystyrene resin Amberlite XAD-2, followed by redissolution of the concentrate in 60% ethanol. Purification was performed via preparative TLC using sequential solvent systems (chloroform and 12.5% ammonia), followed by analytical TLC in a butanol:acetic acid:water (3:1:1) system on silica gel plates (Merck, Germany). Spots were visualized under UV and visible light using a TLC spectrodensitometer, scraped off with the carrier, dissolved in 60% ethanol, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm to precipitate the sorbent. The supernatant was evaporated and weighed. Calibration curves were constructed using standards: avermectin B1a (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), nystatin (Carl Roth, Germany), and doxorubicin hydrochloride (Cayman Chemical, USA). All procedures were performed in triplicate, and sorbents were activated at 105°C prior to use.

2.3. Phytohormones Composition of Soil Streptomycetes Biomass

Preliminary purification and concentration of phytohormones extracted from the biomass of Streptomyces strains were performed through TLC as described earlier [17]. Samples were analyzed by HPLC, exploiting an Agilent 1200 liquid chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an Agilent G1956B Mass Spectrometry (MS) detector. Phytohormone analysis was performed using chemically pure compounds (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany): indole-3-acetic acid, indole-3-acetic acid hydrazide, indole-3-carbinol, indole-3-butyric acid, indole-3-carboxaldehyde, indole-3-carboxylic acid, and cytokinins: zeatin, zeatin riboside, N6-(Δ2-Isopentenyl)adenine, and N6-isopentenyladenosine.

2.4. Sterols Composition of Metabolic Bioproducts

The sterol content in bioproducts derived from the studied Streptomyces strains was determined using GC, following previously established protocols [17]. Sterol compounds were identified by retention time according to the parameter for the standard sterol mixture in the composition: squalene, β-sitosterol, ergosterol, stigmasterol, cholesterol, and 24-epibrassinolide (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany).

2.5. Lipid Composition of Metabolic Bioproducts

Lipid content was determined using a modified Bligh and Dyer extraction method [19]. Briefly, dried biomass (100 mg) was homogenized in a chloroform:methanol mixture (2:1, v/v), followed by phase separation with distilled water. The organic phase was collected, evaporated under reduced pressure, and the lipid residue was weighed gravimetrically. For qualitative analysis, lipid extracts were subjected to TLC on silica gel plates (Merck, Germany) using hexane:diethyl ether:acetic acid (80:20:1, v/v/v) as the mobile phase. Lipid classes were visualized by spraying with 10% sulfuric acid and heating at 120°C.

2.6. Analysis of Phytostimulating Effects of Metabolic Bioproducts

The plants of tomato (L. esculentum Mill.), Ukrainian cultivar Lahidny, were used as the plant material in this study. The seeds were surface-sterilized by immersing them in 70% ethanol for 2-3 minutes, followed by a 5% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution for 15 minutes. The sterilized seeds were then germinated in Petri dishes on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium [20], supplemented with microbial bioproducts: Phytovit, Violar, Averkom, and Averkom nova at the most effective concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 µL/L for tomato shoot regeneration on MST1 medium in vitro. Hypocotyl segments from 10-day-old tomato seedlings were used as plant explants. For shoot regeneration, the explants were placed on MST1 medium [21], based on MST medium and supplemented with 1 mg/L of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and 1 mg/L of zeatin (control), or on MST1 medium supplemented with the studied bioproducts at concentrations ranging from 10 µL/L to 100 µL/L. Starting from the fifth week, the efficiency of tomato plant shoot regeneration (expressed as a percentage) was calculated. The rooting of regenerated tomato plants was conducted on MST1 media supplemented with 100 µL/L of Phytovit and Violar, 25 µL/L of Averkom, and 10 µL/L of Averkom nova.

2.7. Analysis of Tomato Plant Resistance to the Nematode M. Incognita

Regenerated tomato plants were tested for resistance against root-knot nematode, M. incognita; for this purpose, tomato plant leaves and stems were weekly inoculated by spraying with a nematode larval suspension using a hand sprayer (5 mL per plant), as described in a previously published protocol. Resistance against nematodes was evaluated using phenological indices such as plant viability. The parameter was measured at the conclusion of a three-week observation period as a percentage of surviving tomato plants grown on the artificial invasive background on MST1 media, with or without microbial bioproducts, in relation to the total number of tested plants.

2.8. Analysis of the Synthesis of si/miRNA in Tomato Plants and Their Silencing Activity

The molecular-genetic characteristics of resistance in regenerated tomato plants were established. For this purpose, si/miRNA were isolated from both control tomato plants, which were regenerated on MST1 medium containing 1 mg/L of indole-3-acetic acid and 1 mg/L of zeatin, and experimental tomato plants, which were regenerated on MST1 media without or with the supplementation of microbial metabolic bioproducts at concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 µl/L. These si/miRNAs were analyzed to assess the plant resistance [15, 22]. Dot blot hybridization of total cytoplasmic mRNA isolated from control tomato plants with 33P-labelled in vivo using Na2H33PO4 si/miRNA isolated from control and experimental tomato plants was performed. Hybridization experiments were conducted on Millipore AP-15 glass fiber filters (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, UK) as previously described [15, 22]. Silencing activity was quantified as a decrease in the level of incorporation of [35S]-methionine into proteins de novo synthesized on the mRNA template isolated from a plant or nematode in a wheat germ cell-free translation system in vitro [15]. The level of radioactivity of polypeptides (measured as cpm/1 ug of protein) was determined using a Millipore AP-15 glass fiber filter and toluene scintillator in a Beckman LS-100C scintillation counter.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicate (n = 3). Each value was presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Differences in mean values between control and experimental plants were tested using the Student’s t-test. Statistical data analysis was performed using R version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Quantification of Antibiotics Synthesized by Streptomyces Strains

The accumulation of antibiotics in the biomass of three Streptomyces strains was determined under cultivation in synthetic and organic nutrient media (Table 1).

The polyene producer S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025 accumulated significantly more polyene antibiotic when grown in organic medium (2850.6 ± 17.8 µg/g of ADB – absolutely dry biomass) than in synthetic medium (495 ± 7.4 µg/g ADB). In contrast, the anthracycline-producing S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027 showed higher accumulation in synthetic medium (1806 ± 14.2 µg/g ADB) compared to organic medium (426.7 ± 6.9 µg/g ADB). The macrolide producer S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 exhibited a moderate difference between media types, with yields of 854 ± 11.2 µg/g ADB in synthetic medium and 1650 ± 9.3 µg/g ADB in organic medium. The identified avermectins provide a comprehensive approach to direct parasite control by targeting different stages of the parasite's life cycle or different physiological pathways.

| Producer | Class of Anabiotics | Concentrations, µg/g ADB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Nutrient Medium | Organic Nutrient Medium | ||

| S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025 | Polyenes | 495+ 7.4 | 2850.6+ 17.8 |

| S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027 | Anthracyclines | 1806±14.2 | 426.7+ 6.9 |

| S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 | Macrolides | 854±11.2 | 1650±9.3 |

Note: *Within each row, the means (± SD, n = 3), ADB – Absolutely Dry Biomass.

3.2. Composition of Bioproducts Based on Metabolites of Soil Streptomycetes

The composition of metabolic bioproducts based on soil streptomycetes was analyzed. These strains are producers of natural products with potential for plant growth, promotion, and protection against parasitic nematodes and phytopathogens (Table 2).

The standardization of bioproducts is based on the quantity of antibiotics present [14]. Specifically, Phytovit contained 500 µg/mL of polyene antibiotics that are the sum of heptaene and tetraene compounds, Violar contained 500 µg/mL of anthracycline antibiotics, and Averkom contained 100 µg/mL of avermectins. The highest levels of phospholipids, mono- and diglycerides, sterols, sterol esters, and fatty acids were characteristic of Averkom, while they were present in smaller amounts in other bioproducts. Phytovit and Violar contained squalene, cholesterol, ergosterol, sitosterol, stigmasterol, and 24-epibrassinolide, which are important components of cell membranes (Table 2) [12]. It should be emphasized that Averkom did not contain squalene, sitosterol, and stigmasterol. However, the amount of 24-epibrassinolide was significantly higher than in other bioproducts, amounting to 5.66 µg/mL. Table 2 also shows the content of growth-regulating phytohormones in the studied bioproducts: auxins, cytokinins, and the anti-stress phytohormone abscisic acid. The amount of auxins and cytokinins was identified in Phytovit, Violar, and Averkom; their sum was the highest in the last one, amounting to 12.85 µg/mL and 134.8 µg/mL, respectively. This indicates the potential of these metabolic bioproducts to stimulate plant growth and development and to produce safe agrifood.

3.3. Phytostimulating and Phytoprotective Effects of Metabolic Bioproducts

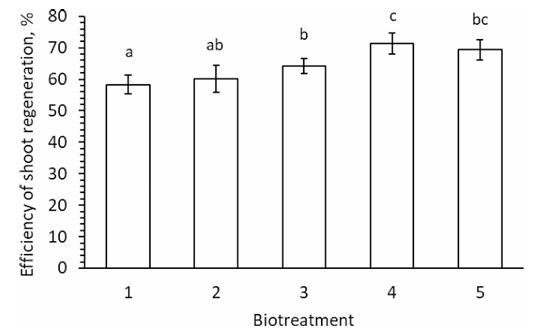

The regeneration of shoots isolated from hypocotyl explants of 10-day-old tomato plants was investigated on MST1 nutrient medium and supplemented with bioproducts, while control plants were not treated with metabolic bioproducts. The differences were determined using Bonferroni corrections (Post-Hoc Test) and are reported as mean ± SD, with p ≤ 0.007 (Fig. 1).

The results indicate that adding the Averkom bioproduct at a concentration of 25 µL/L (or its derivative Averkom nova at 10 µL/L) to the nutrient medium had no significant impact on shoot regeneration after five weeks of cultivation compared to the control. Control plants treated with 1 mg/L IAA and 1 mg/L zeatin showed a lag in shoot formation by the fifth week of tomato plant tissue cultivation. The regeneration efficiency of tomato plant shoots reached 58-60% of that in the control group. Additionally, 100 µL/L of Phytovit and 100 µL/L of Violar lifted the value to 71% (Fig. 1).

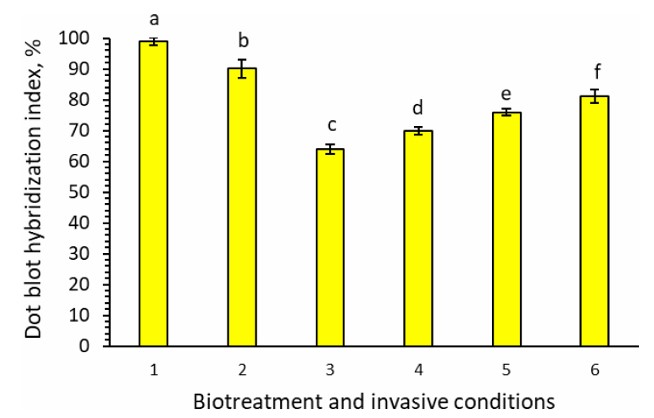

A study of phenological indices, such as plant viability, showed that tomato plants grown on MST1 medium with supplementation of metabolic bioproducts exhibited significantly improved resistance to M. incognita invasion. Plant viability increased to 73-89% for tomato plants grown on MST1 medium supplemented with Averkom, Phytovit, and Violar under invasive conditions, compared to only 27% for plants grown on the same medium without supplements. To explore tomato plant resistance against the root-knot nematode M. incognita, the index of dot blot hybridization (the level of radioactivity of hybrid molecules that was measured as counts per minute/20 ug of mRNA) between cytoplasmic mRNA from control plants and si/miRNA from both control and experimental plants was determined (Fig. 2).

The efficiency of regeneration of shoots of tomato plants grown in vitro on the MST1 media in five weeks supplemented with biotreatment: 1. 1 mg/L of IAA and 1 mg/L of zeatin (control group); 2. 10 µL/L of Averkom nova added to the control group; 3. 25 µL/L of Averkom added to the control group; 4. 100 µL/L of Phytovit added to the control group; 5. 100 µL/L of Violar was added to the control group.

| Components | Phytovit | Violar | Averkom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids, % of total content | |||

| Phospholipids | 19.0 ± 1.5 | 18.0 ± 1.4 | 29.0 ± 1.3 |

| Mono- and diglycerides | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 0.9 | 10.0 ± 0.8 |

| Triglycerides | 59.0 ± 2.3 | 50.0 ± 2.4 | 14.0 ± 0.9 |

| Sterols | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 22.0 ± 1.2 |

| Sterol esters | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 9.0 ± 1.0 | 10.0 ± 0.8 |

| Fatty acids | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 10.0 ± 0.8 |

| Squalene and sterols, µg/mL | |||

| Squalene | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | N/D |

| Cholesterol | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 1.69 ± 0.33 |

| Ergosterol | 5.94 ± 0.71 | 1.29 ± 0.23 | 2.13 ± 0.36 |

| Sitosterol | 0.28 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | N/D |

| Stigmasterol | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | N/D |

| 24-epibrassinolide | 0.58 ± 0.15 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 5.66 ± 0.59 |

| Phytohormones, µg/mL | |||

| Sum of auxins | 2.74 ± 0.55 | 3.61 ± 0.63 | 12.85 ± 0.89 |

| Sum of cytokinins | 3.03 ± 0.58 | 1.93 ± 0.46 | 134.8 ± 2.9 |

| Gibberellins | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 1.26 ± 0.03 | 4.5 ± 0.53 |

| Abscisic acid | 0.03 ± 0.003 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.0023 ± 0.0005 |

Note: Within each row, the means (±SD, n = 3), N/D – Not Detected.

Index of dot blot hybridization between mRNA isolated from control tomato plants and 33Р-labelled si/miRNA isolated from tomato plants grown in vitro on the MST1 nutrient medium: 1. Untreated plants, invasive-free conditions (control); 2. Untreated plants, invasive conditions; 3. Invasive conditions, treatment with 10 µL/L of Averkom nova; 4. Invasive conditions, treatment with 25 µL/L of Averkom; 5. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Phytovit; 6. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Violar.

The dot blot hybridization index shows the level of hybridization between two different types of RNA: mRNA and si/miRNA, and is used to measure the degree of similarity and binding between these molecules (Fig. 2). The percentage value of the dot blot hybridization index indicates how well the mRNA from control plants interacts with the de novo synthesized si/miRNA from both control and experimental plants. An increase in the index value indicates stronger hybridization and, consequently, a greater amount of si/miRNA complementary to the mRNA of control plants, which may indicate their role in regulating gene expression. A reduction in the hybridization index between mRNA from control plants and si/miRNA from experimental plants may reflect an elevated abundance of the de novo synthesized si/miRNA species that inhibit the translation of nematode-associated mRNAs in the experimental group. This shift could signify enhanced post-transcriptional silencing mechanisms, potentially indicating increased resistance of the plants to nematode parasitism [15]. While the index of dot blot hybridization for control plants grown under invasive-free conditions was 99%, this reduced to 90% when an invasive background was introduced (Fig. 2). In experimental plants grown in vitro under invasive conditions supplemented with bioproducts, this index was further reduced to 81% for Violar, 76% for Phytovit, 70% for Averkom, and 64% for Averkom nova (Fig. 2). This indicates an increase in the level of de novo synthesized si/miRNA, complementary to plant mRNA, involved in nematode parasitism.

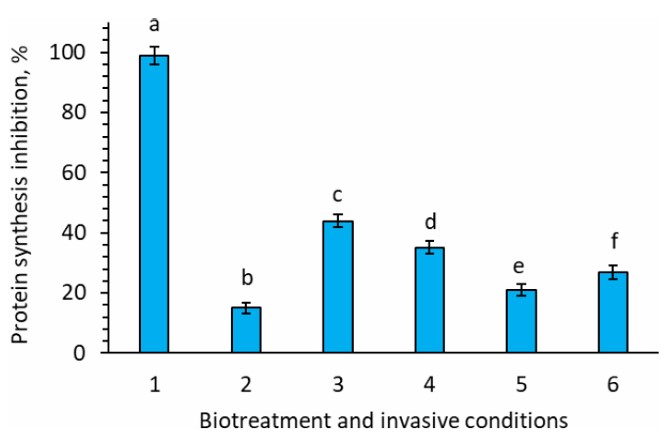

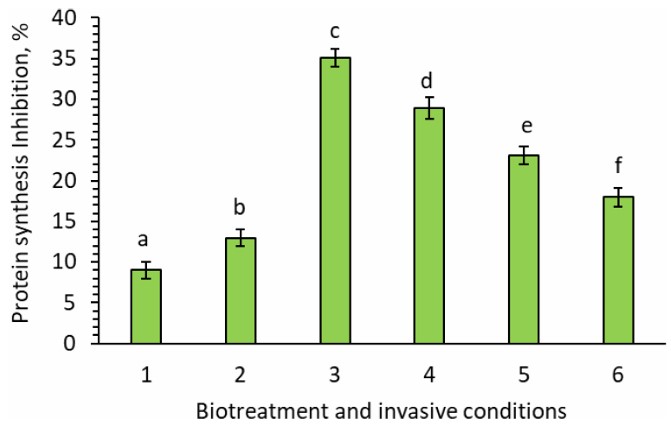

Additionally, the silencing activity of si/miRNA isolated from both control and experimental tomato plants on the inhibition of translation of plant mRNA or nematode mRNA was investigated in the wheat-embryo cell-free protein synthesis system in vitro (Fig. 3). The silencing activity of plant-derived si/miRNA was assessed based on their impact on polypeptide synthesis, using plant-derived mRNA as a translational template, and expressed as a percentage of inhibition of protein synthesis on the template of mRNA of plants, measured as cpm/1 μg of protein.

For si/miRNA and mRNA isolated from control tomato plants, the silencing activity reached 99% (Fig. 3). However, when invasive conditions were introduced, the silencing activity dropped to 15%, indicating that si/miRNA synthesized in experimental plants grown without adding bioproducts were less capable of silencing complementary plant mRNA involved in supporting parasitism (Fig. 3). The supplementation of bioproducts to the nutrient medium during the in vitro cultivation under invasive conditions resulted in an increase in the silencing activity of si/miRNA isolated from these plants to 21% for Phytovit, 27% for Violar, 35% for Averkom, and 44% for Averkom nova (p < 0.007) (Fig. 3).

For si/miRNA isolated from experimental plants grown under invasive conditions without adding any bioproducts, the silencing activity on the mRNA template of nematode increased to 13% (Fig. 4). It was quantified as the percentage inhibition of protein synthesis and measured as cpm/1 μg of protein in a wheat germ cell-free protein synthesis system, expressed as counts per min/1 ug of protein.

This suggests that si/miRNA produced by such plants, when consumed by nematodes during feeding on plant sap, is better able to silence the translation of nematode mRNA. For tomato plants cultivated on the MST1 medium supplemented with metabolic bioproducts under invasive conditions, the silencing activity of si/miRNA isolated from these plants increased to 18% for Violar, 23% for Phytovit, 29% for Averkom, and 35% for Averkom nova (p < 0.008) (Fig. 4). Thus, si/miRNA isolated from experimental tomato plants cultivated in vitro under invasive conditions without bioproduct supplementation exhibited a stronger silencing effect on M. incognita mRNA, and adding bioproducts further increased si/miRNA's ability to silence nematode mRNA. This indicates that the use of bioproducts can be an effective method to increase plant resistance against nematodes.

4. DISCUSSION

Given the increasing yield losses and the significant challenges for sustainable crop production, developing new plant lines with enhanced resistance against pathogens and pests is crucial. A promising solution lies in employing microorganism-based biological products, which offer a sustainable and efficient approach to boosting agricultural yields [16]. Among the various approaches, increased resistance against phytopathogens and parasitic nematodes can be achieved in in vitro–derived plants through treatment with microbial metabolites [23].

The composition of metabolic bioproducts based on secondary metabolites of S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025, S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 was studied; polyenes (candidine and a tetraene compound [18], anthracycline antibiotics, and macrolide antibiotics were quantified in their biomass. The presence of these metabolites in the biomass extracts exerts a direct antagonistic effect on phytopathogenic microorganisms or plant-parasitic nematodes. For example, avermectin antibiotics have a direct neuroparalytic effect on nematodes, making averkom bioproduct important for nematode biocontrol. Treating plants with bioproducts containing microbial phospholipids, mono- and diglycerides, sterols, sterol esters, and fatty acids may contribute to maintaining membrane structure in plant cells, increasing their resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Mono- and diglycerides can improve the adhesion of metabolic bioproducts to the plant surface, providing a longer-lasting protective effect [24]. Additionally, sterols and sterol esters can stabilize cell membranes and enhance resistance against pathogens. The composition of the bioformulations was found to contain the steroidal phytohormone 24-epibrassinolide, with the highest content detected in Averkom. This is extremely important due to its role in enhancing plant resilience. These brassinosteroids contribute to plant resistance by improving photosynthesis and protecting chloroplast ultrastructure, along with other benefits [25]. It regulates the expression of genes associated with plant defense, stimulates the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes that reduce oxidative stress caused by infection, and may enhance signaling pathways related to induced resistance, including RNAi mechanisms [25, 26].

The content of squalene and sterol in the metabolic bioproducts was also studied, and as reported, they can be used in approaches to nematode biocontrol [27]. Plant-parasitic nematodes and pathogens, which are extremely harmful in agriculture, have lost the ability to synthesize their own sterols. Several molecular and biochemical investigations have suggested promising strategies by targeting host sterol composition or its modification in organisms unable to synthesize them de novo. Such modified sterols for plants could be bacterial sterols. Soil streptomycetes synthesized growth-regulating phytohormones (auxins, cytokinins, gibberellins, etc.) with antistress abscisic acid. They act not only as stimulators of growth and development but also as key regulators of plant immunity by inducing the synthesis of ethylene, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid [8, 28]. Elevated cytokinin levels are known to enhance plant resistance to biotic stresses. Such protection is achieved through restoration of hormonal balance disrupted by stressors [29, 30]. The experimental effects of metabolic bioproducts can be attributed to the combined action of plant hormones and other bioactive components, with biotreatment of in vitro–cultured tomato plants resulting in improvement of morphometric parameters of seedlings and enhanced resistance to nematodes due to an increase in de novo synthesized anti-nematode si/miRNA in tomato cells [22, 31, 32].

Silencing activity of si/miRNA obtained from tomato plants grown in vitro in a wheat germ cell-free protein synthesis system, expressed as counts per min/1 μg of protein. 1. Untreated plants, invasive-free conditions (control); 2. Untreated plants, invasive conditions; 3. Invasive conditions, treatment with 10 µL/L of Averkom nova; 4. Invasive conditions, treatment with 25 µL/L of Averkom; 5. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Phytovit; 6. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Violar.

The silencing activity of si/miRNA isolated from in vitro-grown tomato plants on the template of M. incognita. 1. Untreated plants, invasive-free conditions (control); 2. Untreated plants, invasive conditions; 3. Invasive conditions, treatment with 10 µL/L of Averkom nova; 4. Invasive conditions, treatment with 25 µL/L of Averkom; 5. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Phytovit; 6. Invasive conditions, treatment with 100 µL/L of Violar.

The morphogenic potential of cultured explants, particularly their shoot regeneration efficiency, depends on various factors. One significant factor is the age of the plants from which explants are obtained. This study used segments of hypocotyls from 10-day-old tomato seedlings as explants. Previous research has also shown that the efficiency of tomato shoot regeneration in vitro depends on the type of explants, the class and concentrations of phytohormones, and plant genotypes. Earlier studies reported that the highest number of regenerated tomato plant shoots was obtained on Murashige and Skoog medium supplemented with zeatin and IAA [20]. Experimental observations support these findings, demonstrating the highest efficiency of tomato shoot regeneration on MST1 medium supplemented with 1 mg/L of IAA and 1 mg/L of zeatin. Furthermore, the efficiency of tomato plant shoot regeneration increased when the nutrient medium was supplemented with zeatin, and metabolic bioproducts were added that were associated with the plant growth–promoting activity of streptomycetes secondary metabolites [33]. Previous studies on various agricultural and vegetable crops have shown that natural metabolic bioproducts significantly increase the resistance of plants to pathogens and pests by inducing RNA interference (RNAi) in their cells. This is achieved by stimulating the biosynthesis of endogenous si/miRNA, which silences the mRNA of pests and pathogens [15]. These studies also demonstrated the potential of using microbial bioproducts to develop wheat lines with RNAi-mediated resistance to Heterodera avenae under in vitro conditions [22]. This study has shown that, besides positively affecting shoot regeneration, tomato plants grown on MST1 medium supplemented with Averkom, Phytovit, and Violar under invasive conditions exhibited significantly higher plant viability, reaching 73-89%, compared to only 27% of control plants grown on the same medium without supplements, indicating RNAi-mediated resistance to M. incognita invasion.

Dot blot hybridization was performed to gain further insights into RNAi-based protection of tomato plants against the plant parasitic nematode M. incognita. The experiments revealed that tomato plants grown in vitro on MST1 medium supplemented with metabolic bioproducts exhibited significantly increased levels of si/miRNA synthesis, which is complementary to both plant mRNA and nematode mRNA. Given the noticeable reduction in nematode invasion associated with the use of metabolic bioproducts in vitro, it is likely that these de novo synthesized si/miRNAs target a network of plant genes that facilitate nematode parasitism, including nematode housekeeping genes, genes associated with parasitism, and effector transcripts specifically activated during the early stages of M. incognita penetration into plant cells [34-36]. Supporting evidence was obtained from in vitro assays using a wheat germ cell-free translation system, which confirmed the proposed mechanism by demonstrating markedly stronger inhibition of protein synthesis on both plant and M. incognita mRNA templates by plant-derived si/miRNA. These results confirm that applying microbial biostimulants to the MST1 nutrient medium can produce new lines of tomato plants with increased viability and RNAi-mediated resistance to nematode invasion.

Metabolic bioproducts derived from soil Streptomyces demonstrate significant potential for protecting tomatoes and other crops against nematodes under field conditions. Due to the presence of phytohormones such as cytokinins and brassinosteroids, along with bioactive lipids, these bioproducts not only suppress pathogens but also promote plant growth and resilience. Their application may reduce dependence on chemical pesticides, thereby supporting sustainable agricultural practices, and they can be incorporated into biocontrol strategies as components of integrated crop protection systems [30, 32]. Use in nurseries and greenhouses for the pre-treatment of plants prior to transplantation into the field also represents a promising approach [37]. However, several limitations must be considered. The efficacy observed under controlled laboratory conditions may not fully translate to open-field environments, where complex ecological interactions occur. The stability of bioactive metabolites in soil is often limited, as they may degrade rapidly or bind to soil particles. In addition, specificity remains restricted, with strong activity against certain pathogens or nematodes but not universally across all crops [38]. To summarize, metabolic bioproducts of S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025, S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015 not only facilitate plant growth and development but also contribute to the formation of plant immunity and the effective functioning of signaling networks associated with molecular responses to pathogens. This is achieved through the transmission of elicitor signals that activate the de novo synthesis of plant si/miRNAs protective against the parasitic nematode M. incognita.

CONCLUSION

This study identified bioactive compounds produced by S. netropsis IMV Ac-5025, S. violaceus IMV Ac-5027, and S. avermitilis IMV Ac-5015, including antibiotics, and developed bioproducts such as Phytovit, Violar, Averkom, and Averkom nova. The biochemical properties of these metabolites were characterized, and their phytoprotective effects against M. incognita were demonstrated in vitro. Gene silencing assays confirmed RNAi-mediated resistance in tomato plants regenerated on bioproduct-supplemented medium, highlighting the role of elicitor signals in activating de novo synthesis of protective si/miRNAs. Overall, secondary metabolites of soil streptomycetes promote plant growth, strengthen immunity, and support signaling networks involved in pathogen defense. These findings provide a basis for eco-friendly technologies targeting root-knot nematodes and for developing resistant crop lines to advance sustainable agrifood production. Their application of these metabolic bioproducts may reduce reliance on chemical pesticides, support sustainable agricultural practices, and be incorporated into biocontrol strategies. However, field efficacy may differ from laboratory results due to ecological complexity, limited stability of metabolites in soil, and restricted specificity across crops.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: G.I., L.B., and Y.B.: Study conception and design; L.B., M.L., G.I., V.T., A.S., K.B., E.S., S.S., and A.Y.: Data collection; G.I., M.L., Y.B., V.T., and A.Y.: Analysis and interpretation of results; G.I., L.B., M.L., R.M., and V.T.: Draft manuscript; G.I., M.L., and R.M.: Formal analysis; M.L., G.I., V.T., and Y.B.: Writing, reviewing, and editing; All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| siRNA | = small interfering RNA |

| miRNA | = microRNA |

| mRMA | = messenger RNA |

| TLC | = Spectrodensitometric Thin-Layer Chromatography |

| HPLC | = High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| GC | = Gas Chromatography |

| MS | = Murashige and Skoog medium |

| MST1 | = Modified MS medium, type 1 |

| IAA | = Indole-3-Acetic Acid |

| Cpm | = Counts per minute |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Supplementary information is available from the corresponding author [M.L.] on a reasonable request.

FUNDING

This study was supported by state-funded projects of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, as specified in the Funding section of the manuscript This work was financially supported through the Fundamental Departmental Program: Ecosystem functions of soil microbiome in restorative agroecosystems in 2025-2030 (0125U000938), of the NAS of Ukraine, the interdisciplinary program of the NAS of Ukraine on Molecular and cellular biotechnologies for medicine, industry, and agriculture for 2015-2019, within the project Production of cell lines of agricultural plants with increased resistance to pathogenic and parasitic organisms by inducing RNA interference using bioregulators of microbial origin.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Yaroslav Blume is the Editor in Chief of The Open Agriculture Journal.

Dr. Alla Yemets is the Editorial Advisory Board member of The Open Agriculture Journal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Actinobacteria Metabolic Engineering Group of the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (Saarbrücken, Germany) and the Data Intensive Science Centre at the University of Sussex. M L is grateful to the National Scholarship Programme of the Slovak Republic for the mobility grant (ID 51176). The work is also supported by the Joint Ukrainian-German R&D Projects for the period of 2024–2025, “Microbial biologically active metabolites as a biotechnology tool to improve crop productivity and soil health recovery (MicroMet).”