All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Plant and Soil Metal Concentrations in Serpentine Soils and Their Influence on the Diet of Extensive Livestock Animals

Abstract

Background:

Grazing circuits and resources consumed differ strongly throughout the year and within a territory. For this reason, animals’ diet composition, as well as their exposure to metals, is variable. No studies have been performed on how habitat use affects the metal concentrations to which sheep and goats reared in serpentine soil areas are exposed.

Objective:

The aim of the present study was to investigate the metal exposure of grazing animals raised in a serpentine soil area of the north-east of Portugal, taking into account the spatial distribution of metal concentrations in soils and plants.

Methods:

The habitat use and foraging behaviour of six flocks of sheep and goats were studied. The concentrations of Ca, Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni were determined in the soils and plant species most consumed by those animals.

Results:

The highest Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni concentrations were found in the soils of the ultramafic complex. Ni concentrations above the recommended threshold for agricultural soils (30 μg/g) were found in some sites. A positive correlation between Ni concentration in soils and plants was found (0.634). Ni concentrations higher than 10 µg/g were found in some samples of the following plant species: Sorghum × drummondii (Steud.) Millsp. & Chase,Quercus rotundifolia Lam., Cytisus multiflorus (L’Hér.) Sweet, Cistus ladanifer L. and Erica scoparia L. Significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in metal concentrations of the plants most consumed by each flock were observed.

Conclusion:

Grazing circuits have an important role in the metal exposure of animals raised in this serpentine soil area.

1. INTRODUCTION

Serpentinites are an uncommon lithology that occurs in very specific geodynamic environments, typically defining alignments, and exhibiting a typical greenish colour. Serpentine soils are found worldwide but have patchy distribution, covering less than 1% of the total land surface [1]. In Portugal, serpentinites are known to occur in the Bragança-Morais massif and Beja-Acebuches ophiolitic complex [2].

Soils that develop on this parent material are deficient in some macronutrients, show imbalances in nutrient elements (low Ca : Mg ratios) and display toxic concentrations of metals such as chromium (Cr) and nickel (Ni) [3]. Vegetation grown on these soils may accumulate high levels of metals, thereby causing potential health hazards for grazing animals and humans [4, 5].

Vegetation and serpentine soils have been studied extensively [6-8]. Outcomes have revealed high concentrations of potentially biologically toxic elements such as Cr and Ni, poor plant productivity and specific kinds of vegetation [9, 10]. Significant differences in plant metal uptake between plant species have been observed [11-14]. Also, metal accumulation in animal tissues of grazing animals raised on serpentine or other contaminated areas has been investigated [15, 16]. Cr, Ni and manganese (Mn) are essential elements for life and are involved in different metabolic processes [16, 17]; however, they may be toxic in excess.

Grazers are exposed to these metals via ingestion of contaminated vegetation and small amounts of soil, and in some cases also via drinking water [18]. López-Alonso et al. [19] pointed out that toxic metal accumulation in animal tissues is directly related to grazing activity, and toxic metal exposure through soil ingestion could be higher than the one through the diet. On the other hand, the choice of food plants may in some cases affect the metal exposure of herbivorous animals more than that reflected by the general contamination level in the area [20, 21].

In the north of Portugal, the small ruminant production system is based on the exploitation of rangeland resources and by-products of agriculture. In this region, small ruminants are produced by landless farmers or smallholders. In this way, the livestock system is supported by grazing itineraries over unfenced or uncultivated village territory [22]. Flocks are conducted by shepherds, crossing land with different uses [23]. Grazing circuits and resources consumed differ strongly throughout the year and within a territory. For this reason, diet composition, as well as animals’ exposure to metal, is variable.

No studies have been performed on how habitat use affects metal concentrations to which sheep and goats reared in serpentine soil areas are exposed. In order to get knowledge on this subject, in the present work, six herds (three of sheep and three of goats) were followed to find out their grazing circuits and diets. At the same time, soil and vegetation samples were collected, and the metal concentrations (Ca, Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni) in them determined in order to evaluate the animals’ metal exposure. In more detail, we want to find out which plant species and grazing circuits are more problematic to animals in terms of heavy metals, namely chromium and nickel.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Area and Flock Description

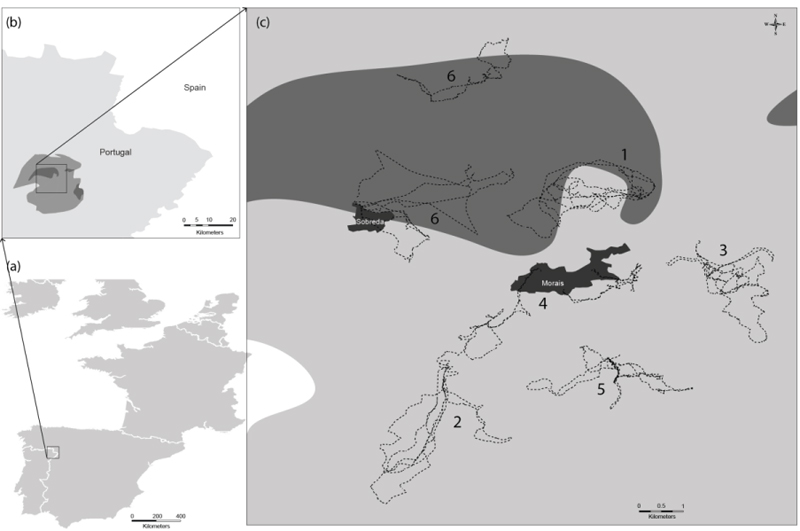

The present study was carried out in the Morais region (41° 29' N, 6° 46' W), a serpentinic area in the north-east of Portugal (Fig. 1). The mean annual temperature is 11.9 °C and the mean rainfall is 636 mm [24]. The dry period occurs mainly in July and August. Morais geomorphology is characterized by an undulating plateau (mean altitude 600 m), cut by two rivers, the Azibo and Sabor [25].

Extensive livestock farming is one of the main economic activities based on common lands, native pastures and by-products of agriculture. Subsistence farming is the dominant type of agriculture. Winter cereals (wheat and rye) and spring crops (maize, potatoes or vegetables) are produced on several plots. Also, Olea europaea L. (olive) groves appear in small areas, frequently close to vineyards and other kinds of orchard.

2.2. Grazing Circuits and Diet Composition

Grazing circuits cross a set of habitats (i.e. different land uses or kinds of vegetation) that spread along Morais village territory (home range). Taking into account the geographical distribution of stables over the territory of Morais village, determined previously by Castro [26], six flocks were selected: three of goats (Serrana breed, Flocks 1 to 3) and three of sheep (Churra Terra Quente breed, Flocks 4 to 6). These flocks had variable size (100 to 200 animals/flock) and had been raised for meat production.

The flocks were monitored every 3 months for a year in order to determine their grazing circuits and diet composition. Field observations were made in September (autumn) 2010, January (winter), April (spring) and July (summer) 2011. To determine the length and duration of grazing circuits, each herd was recorded for one day per season by means of a hand-held Global Positioning System (GPS). The GPS data comprised time, geographical position and land cover of 24 herd itineraries in total. The animals were followed from they went out for grazing until their return to the stable. Measurements during the day were done every 15 min. The grazing journey varied from 576 min in autumn to 360 min in winter.

Diet composition was determined by a direct observation method, following the methodology of Meuret et al. [27], with slight modifications. The scan-sampling method proposed by Altmann [28], consisting of systematic sampling at pre-set time intervals and regular records, was followed in the present work. At each temporal observation point, two observers recorded the activity of 10 animals randomly chosen in a quadrant (i.e. N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW). The set of animals and quadrant changed every 15 min. If animals were feeding, the plant species (or ‘facies’) consumed were recorded, as proposed by Agreil and Meuret [29]. Five herbaceous communities were considered: i) herb, mainly composed of spontaneous grasses and forbs, ii) cereal fallow, iii) meadow, iv) cereal stubble and v) other forage. As proposed by Castro [23], diet composition was calculated by the ratio of the number of animals that were feeding on a plant species and the total number of animals that were in feeding activity.

2.3. Soil and Plant Collection

After determining the grazing circuits and the plant species most consumed, four sampling sites were chosen in each of the 24 grazing circuits, for collection of soils and plants. The plant species sampled were Sorghum × drummondii (sorghum), holm oak, Cytisus multiflorus, Cistus ladanifer, Erica scoparia, olive, Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn., Genista hystrix, Avena sativa L. and Rubus ulmifolius Schott. Also, the five herbaceous communities described before were sampled.

Soils and plants were collected at the same point in late September/October 2010, January/February 2011, April/May 2011 and July 2011, 192 samples being collected in total (96 soils and 96 plants). At each sampling site, 1 L of soil was collected at a depth of 10 cm using a stainless steel shovel and stored in a plastic bag. Regarding plants, at each site, a representative sample of each species or community type, namely in the case of herbaceous groups, was collected by cutting with stainless steel scissors from 1 cm above the soil.

2.4. Soil and Plant Analysis

Soil analysis was carried out on air-dried soil and the ≤ 2-mm fraction (fine earth fraction) of samples. Soil pH was measured in water and 1 M KCl using a 1 : 2.5 soil : solution ratio. Ca, Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni in soils were determined by EPA Method 3051A. This is a microwave-assisted leaching method involving the use of HNO3 or a mixture of HNO3 and HCl, comparable to the open-vessel Method 3050B [30]. This acid digestion will dissolve almost all elements that could become ‘environmentally available’.

Plants were oven-dried (60 °C) (Memmert, model 100), ground and sieved (1 mm diameter). For each plant, a 1-g subsample was accurately weighed in Teflon vessels, and concentrated HNO3 (10 mL) was added. Subsequently, samples were digested in a microwave oven (MARS Xpress, CEM). Microwave digestion at 1600 W was completed in two successive steps: 200 °C for 15 min, and holding at this temperature for 15 min. After digestion, the solutions were adjusted to 25 mL with ultra-pure water. Metal concentrations in the digests were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS) (Sprectr AA 220, Varian). For Mg and Ca analysis of soils and plants, lanthanum (La) (1 g/L) was used as a matrix modifier, 10 mL of this solution being added to 500 µL of digest. An analytical quality control program was applied throughout the study. The detection limits in the acid digests were determined, taking into account the lowest standard used. Analytical recoveries were determined from a certified reference material (bush branches and leaves - NCS DC 73349) analysed alongside the samples. The mean recoveries were between 78.1% and 97.0%, showing acceptable agreement between the measured and certified values.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software (v.20.0). Before starting, all data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene tests, respectively. As data for all metal concentrations were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were therefore applied. The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparison of the mean of the orders, was used to evaluate the variation in soil and plant metal concentrations between flocks (grazing areas). In all analyses, statistical significance was taken to be indicated by p ≤ 0.05. A Spearman correlation test was used to evaluate possible correlations between plant and soil metal concentrations. Principal component analysis (PCA) in the CANOCO 4.5 program [31] was applied to evaluate multivariate soil and plant metal concentrations data (96 samples × 12 variables). Results of the multivariate analysis were visualized in the form of a bi-plot ordination diagram created with CanoDraw© software.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Grazing Circuits and Diet Composition

The location of the area studied and grazing circuits of the six flocks are represented in Fig. (1). The grazing circuits of the six flocks crossed different foraging areas, overlapping in particular situations (e.g. Flocks 2 and 4). There were two flocks that always grazed on Morais ultramafic complex (Flocks 1 and 6), Flock 6 changing to another stable in autumn. Ligneous species (e.g.Holm oak, olive tree, Cytisus multiflorus, Cistus ladanifer, Genista hystrix, Erica scoparia, Rubus ulmifolius and Alnus glutinosa) were the main components of goat diet during the year, while in spring this pattern was not so clear. The sheep diet was mostly comprised of herbaceous species (e.g. meadow, sorghum, herbaceous sward, fallows and stubble). Holm oak (leaves and acorns) was one of the resources consumed most by Flock 1 while Flocks 2, 3 (goats) and 5 (sheep) consumed more olive tree resources (leaves, fruits and herbaceous cover). The three resources most consumed seasonally by the six flocks are represented in Table 1.

| Period | Flock |

Plant (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn | 1 | Sorghum 23.0 |

Holm oak leaves 21.2 |

Holm oak acorn 12.7 |

| 2 | Sorghum 24.2 |

Herbaceous sward 20.0 |

Holm oak leaves 20.0 |

|

| 3 | Sorghum 26.3 |

Herbaceous sward 16.1 |

Cistus ladanifer 11.8 |

|

| 4 | Meadow 26.4 |

Sorghum 24.0 |

Olives 13.0 |

|

| 5 | Meadow 33.6 |

Oat 20.5 |

Stubble 13.4 |

|

| 6 | Meadow 44.4 |

Stubble 18.7 |

Herbaceous sward 18.7 |

|

| Winter | 1 | Herbaceous sward 40.8 |

Cistus ladanifer 26.6 |

Erica scoparia 16.0 |

| 2 | Herbaceous sward 36.5 |

Olive tree leaves 21.2 |

Cistus ladanifer 19.7 |

|

| 3 | Herbaceous sward 48.4 |

Olive tree leaves 33.8 |

Cistus ladanifer 10.2 |

|

| 4 | Herbaceous sward 33.3 |

Stubble 25.7 |

Cytisus multiflorus 15.3 |

|

| 5 | Herbaceous sward 80.4 |

Olive tree leaves 13.5 |

Stubble 6.13 |

|

| 6 | Meadow 53.6 |

Herbaceous sward 25.0 |

Cytisus multiflorus 15.6 |

|

| Spring | 1 | Herbaceous sward 40.9 |

Holm oak leaves 30.1 |

Cytisus multiflorus 10.8 |

| 2 | Herbaceous sward 80.2 |

Meadow 14.7 |

Fallows 5.15 |

|

| 3 | Herbaceous sward 50.8 |

Cytisus multiflorus 22.6 |

Meadow 13.1 |

|

| 4 | Herbaceous sward 60.2 |

Meadow 37.6 |

Cytisus multiflorus 2.15 |

|

| 5 | Meadow 45.8 |

Fallows 37.5 |

Herbaceous sward 16.7 |

|

| 6 | Meadow 43.2 |

Herbaceous sward 40.6 |

Cytisus multiflorus 13.0 |

|

| Summer | 1 | Holm oak leaves 39.2 |

Genista hystrix 20.2 |

Erica scoparia 17.7 |

| 2 | Sorghum 23.5 |

Herbaceous sward 20.6 |

Alnus glutinosa 12.4 |

|

| 3 | Meadow 25.2 |

Rubus sp. 25.2 |

Herbaceous sward 13.2 |

|

| 4 | Meadow 54.8 |

Other forages 23.8 |

Olive tree leaves 17.7 |

|

| 5 | Stubble 54.8 |

Oat 31.9 |

Olive tree leaves 9.52 |

|

| 6 | Meadow 62.2 |

Fallows 14.2 |

Erica scoparia 9.84 |

|

3.2. Soil and Plant Metal Concentrations

The concentrations of Ca, Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni, as well as Ca/Mg ratios, determined in soils collected along the grazing circuits of each flock are represented in Table 2. The medians ranged between 1.52 and 3.05 mg/g, 4.28 and 11.6 mg/g, 343 and 728 µg/g, 7.54 and 142 µg/g, 12.3 and 934 µg/g and 0.23 and 2.15, respectively. Significant differences were found in soil metal concentrations (p ≤ 0.05) of the six flocks, with the exception of Ca and Ca/Mg. The highest concentrations of Mg, Cr and Ni were determined in the soils collected from the grazing circuits of Flocks 1 and 6.

| Ca (mg/g) | Mg (mg/g) | Mn (μg/g) | Cr (μg/g) | Ni (μg/g) | pHH2O | pHKCl | Ca/Mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flock | ||||||||

| Flock 1 | 1.52 (0.300-25.0) |

11.3 a (6.60-41.2) |

728a (422-1499) |

113 a (26.5-1016) |

830 a (251-1529) |

6.19 a (4.90-7.47) |

5.22 a,c (4.47-6.49) |

0.160 (0.0300-1.61) |

| Flock 2 | 2.27 (0.100-19.8) |

5.92 b (4.00-17.2) |

366 b (203-913) |

7.54 b (3.79-84.0) |

17.0 b (8.11-175) |

5.96 a,b (4.58-6.94) |

4.92 b,c (3.65-6.17) |

0.420 (0.0300-3.68) |

| Flock 3 | 1.64 (0.100-23.0) |

4.28 b (0.100-10.8) |

501 a (304-2041) |

13.0 b (0.960-39.8) |

12.3 b (1.18-43.0) |

5.99 a,b (4.69-6.90) |

4.84 b (3.73-5.88) |

0.59 (0.190-11.6) |

| Flock 4 | 1.68 (0.100-18.3) |

6.23 b (2.60-8.80) |

384 b (253-523) |

7.70 b (3.65-16.1) |

14.7 b (3.88-24.5) |

6.03 a,b (4.50-7.05) |

4.74 b (3.80-6.24) |

0.360 (0.0100-2.17) |

| Flock 5 | 1.56 (0.300-20.0) |

4.54 b (0.600-15.7) |

343 b (93.8-515) |

8.96 b (0.830-74.7) |

21.6 b (2.47-313) |

5.69 b (4.93-6.46) |

4.88 b (4.22-5.62) |

0.500 (0.0700-26.8) |

| Flock 6 | 3.05 (0.500-15.0) |

11.6 a (2.80-30.2) |

718 a (219-2031) |

142 a (21.9-703) |

934 a (62.1-1737) |

6.20 a (5.19-6.93) |

5.38 a (4.88-6.65) |

0.330 (0.0400-2.60) |

Regarding soil pH determined in water (pHH2O), values varied between 5.69 and 6.20 for Flocks 2 and 6, respectively. Soil pH determined in KCl (pHKCl) was always lower than the pHH2O values, varying between 4.74 and 5.38 for Flocks 4 and 6, respectively.

Concerning the plants most consumed, the metal concentrations by flock are represented in Table 3. Ca, Mg, Mn, Cr, Ni and Ca/Mg medians ranged between 1.35 and 10.9 mg/g, 8.36 and 23.5 mg/g, 42.3 and 126 µg/g, 0.75 and 1.59 µg/g, 2.35 and 18.6 µg/g and 0.06 and 1.04, respectively. Significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in plant metal concentrations were found between flocks.

| Ca (mg/g) | Mg (mg/g) | Mn (µg/g) | Cr (µg/g) | Ni (μg/g) | Ca/Mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flock | ||||||

| Flock 1 | 5.45 b (0.0130-35.8) |

16.6 a,b (5.00-71.4) |

121 a (13.0-515) |

0.750 b (0.140-27.8) |

18.6 a (4.91-51.5) |

0.220 a,c (0.00100-2.10) |

| Flock 2 | 6.10 a,b (0.103-84.3) |

14.2 b,c (6.40-29.3) |

126 a (17.2-833) |

0.750 b (0.160-5.81) |

2.61 b (0.960-7.82) |

0.400 b (0.0170-7.53) |

| Flock 3 | 10.9 a (0.0470-115) |

15.4 a,b (7.40-40.2) |

115 a (18.3-760) |

0.75 b (0.0700-2.46) |

2.35 b (1.23-7.70) |

1.04 b (0.00500-6.33) |

| Flock 4 | 4.94 a,b (0.0410-55.6) |

9.84 b,c (4.40-28.0) |

99.9 a,b (10.3-211) |

1.02 a,b (0.190-7.82) |

2.50 b (0.410-5.02) |

0.500 a,b (0.00500-5.53) |

| Flock 5 | 3.30 b,c (0.00800-68.6) |

8.36 c (2.20-33.2) |

46.9 b (1.64-483) |

1.59 a (0.750-13.6) |

5.00 b (1.17-13.6) |

0.36 a,b (0.00100-7.83) |

| Flock 6 | 1.35 c (0.0400-81.8) |

23.5 a (8.70-46.3) |

42.3 b (12.0-452) |

1.50 a (0.570-18.6) |

10.7 a (1.18-64.0) |

0.0600 c (0.00100-1.64) |

3.3. Relationship Between Metal Concentrations and Foraging Areas

Table 4 shows the Spearman correlation indices between soil and plant metal content. The highest correlations (> 0.7) in soils were found between Ni and Cr (r = 0.802), and Ni and Mg (r = 0.799) concentrations, followed by those between Mg and Cr (r = 0.674), Mn and Cr (r = 0.625) and Mn and Ni (r = 0.614). In plants, Ni concentrations were also correlated positively with Cr (r = 0.680) and Ni (r = 0.631) content in soils. On the other hand, no significant correlations of Cr in plants and soils were found.

| Mg- Soil | Mn- Soil |

Cr- Soil |

Ni- Soil |

Ca-Plant | Mg-Plant | Mn-Plant | Cr-Plant | Ni-Plant | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca-Soil | -0.199* | ||||||||

| Mg-Soil | 0.511** | 0.674** | 0.799** | -0.211** | 0.481** | 0.483** | |||

| Mn-Soil | 0.625** | 0.614** | 0.370** | 0.448** | |||||

| Cr-Soil | 0.802** | 0.429** | 0.680** | ||||||

| Ni-Soil | -0.286** | 0.425** | -0.161* | 0.631** | |||||

| Ca-Plant | 0.229** | 0.169* | |||||||

| Mg-Plant | 0.371** | ||||||||

| Mn-Plant | -0.171* | -0.178* | |||||||

| Cr-Plant | 0.329** |

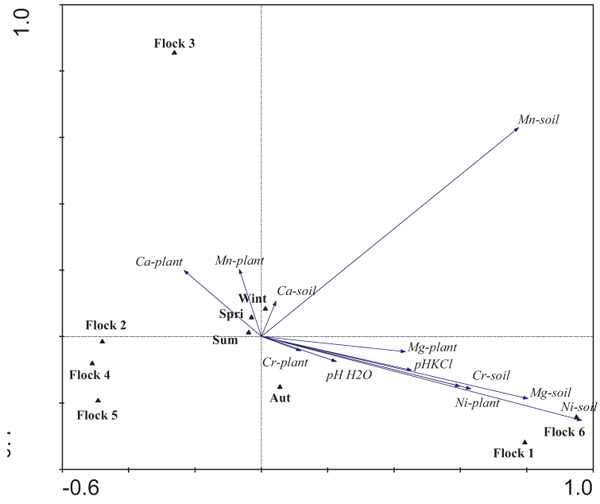

In order to relate grazing circuits, foraging areas and flocks, PCA was done taking into account the metal concentrations of soils and plants (Fig. 2). The first two axes (PC1 and PC2) explained 90.8% of the total variability of the multivariate analysis between both axes (PC1 and PC2 explained 73.5% and 17.3%, respectively). Soil concentrations of Ni and Mg were the most important variables in relation to axis I (PC1), closely followed by Ni plant, and Cr and Mg soil content. The highest content of these metals was found for the foraging areas of Flocks 1 and 6, whereas the lowest values were observed for Flocks 2, 4 and 5. Flock 3 was discriminated along axis II (PC2), revealing higher concentrations of Mn in soil, and Ca and Mn in plants.

4. DISCUSSION

Diet composition varied with the availability of plant species in the habitat (affected by the grazing circuit and season) and with animal species, explaining the different resources consumed by each flock. For example, the grazing circuits of both Flocks 1 (goat) and 6 (sheep) crossed the Morais ultramafic massif but their diet composition differed. It is known that sheep and goats consume different proportions of herbaceous and ligneous species. The former feed more often on herbaceous species than goats. This feeding strategy has been observed in many studies performed in different plant communities [23, 32, 33].

Regarding metal concentrations, a high degree of variability was observed between grazing circuits. Despite all soils coming from a serpentine area, soil composition varied widely between sites; it might depend upon the geological material, as suggested by Lázaro et al. [11]. The highest Mg, Cr and Ni content was found in soils collected from the circuits of the flocks that graze around the Morais ultramafic complex (Flocks 1 and 6). This type of soil is characterized by high concentrations of metals such as Mg, Mn, Cr and Ni [3], explaining the results obtained. Soils were characterized by low Ca/Mg ratios (medians < 1), Ca/Mg ratios less than 1 being characteristic of strongly serpentinized soils [9]. Moreover, the Ca and Mg concentrations determined in the present work were in line with the concentrations determined by Shallari et al. [34] in serpentine soils in Albania (2 to 24 mg/g of Ca and 15 to 25 mg/g of Mg). Regarding Mn, almost all concentrations determined in the present work were within the ranges of 5.5-670 and 660-800 µg/g reported for managed serpentine soils collected in the north-west of Spain [4] and in Iran [12], respectively. Concerning Cr occurring naturally in soil, this metal ranges from 10 to 50 µg/g, depending on the parental material [35]. In serpentine soils, Cr can reach up to 125 mg/g [35]. Nevertheless, the Cr concentrations found in our study were lower than this value and the range between 365 and 3865 µg/g reported by Shallari et al. [34] for serpentine soils of Albania. On the contrary, the Cr concentrations determined in Morais soils were higher than the range reported by Fernández et al. [4] (0.1-0.9 µg/g), and similar to that reported by Miranda et al. [16] (10.0 to 1162 µg/g) for serpentine soils in the north-west of Spain. Regarding Ni, the levels determined in soils from the circuits of Flocks 2 to 5 were within the range reported by Fernández et al. [4], 5-110 µg/g, for managed serpentine soils of north-west Spain. Nevertheless, much higher Ni concentrations were found in soils from the circuits of Flocks 1 and 6 because the shepherds took their animals to graze around the Morais massif (Fig. 1), an area where ultrabasic rocks predominate and high Ni concentrations are found. The Ni soil medians determined for these two flocks (830 and 934 µg/g) were similar to the range reported by Ghaderian et al. [12] (800-1240 µg/g), to the maximum of 940 µg/g indicated by Miranda et al. [16] and to the median of 1329 µg/g found by Kierczak et al. [36] determined in Iranian, Spanish and Polish serpentine soils, respectively. In addition, the soils collected on the Morais ultrabasic complex had Ni concentrations above the recommended threshold for agricultural soils (30 µg/g) [16], in line with the land use of this territory which is mainly covered by forest and shrub lands. Regarding pH, our pHH2O values were within the range determined by Kataeva et al. [37], 5.45-7.46, in the Polar Urals. Concerning plants, Ca/Mg plant ratios were generally less than 1.0, as observed for soils. As reported by Reeves et al. [13], this proportion is uncommon. The Mn concentrations determined in the present work were within the ranges reported by Fernández et al. [4] (6-300 µg/g) and Lázaro et al. [11] (14.5-2200 µg/g) for plants collected in serpentine soils in the north-west of Spain and north-east of Portugal, respectively. Some plants collected from the Morais site had a Mn content above 300 µg/g, the threshold toxicity level in plants [4]. Almost all Cr plant concentrations determined in the present study were in close agreement with those of Fernández et al. [4] (0.8-11.5 µg/g), Miranda et al. [16] (0.39 to 7.11 µg/g) and Oze et al. [10] (0.003 to 5.76 µg/g) for vegetation collected in several serpentine soils. It is worth mentioning that our low Cr values found in the aerial parts of the plants could be mainly due to Cr accumulating more in roots than in leaves, as Cr is preferentially immobilized, suppressed and/or sequestered into the roots and/or woody tissue [10]. Cr is sequestered in the vacuoles of root cells, thus rendering it less toxic, which may be a natural toxicity response of the plant [35]. The soil Cr concentrations of Flock 5 were much lower than those of Flocks 1 and 6 (Table 2); however, the highest medians of plant Cr were found in Flock 5 (1.59 µg/g) and Flock 6 (1.50 µg/g), suggesting that the low pH values of Flock 5 soils could have accounted for a high soil-to-plant transfer of metals. Nevertheless, the highest Cr concentrations (27.8 and 18.6 µg/g) were determined in sorghum and meadow collected from the grazing areas of Flocks 1 and 6. Regarding Ni, the plants analysed in the present work presented content within the range reported by Ghaderian et al. [12] (55-90 µg/g), Fernández et al. [4] (3-35 µg/g), Miranda et al. [16] (11.1-39.3 µg/g), Reeves et al. [13] (5-275 µg/g) and Oze et al. [10] (0.13-24.4 µg/g) for plants growing in serpentine soils in Iran, Spain, Costa Rica and the USA, respectively. The highest medians were determined for Flocks 1 and 6 and were above the threshold level for toxicity in plants (10 µg/g) [4]. The plants with Ni concentrations higher than 10 µg/g (Table 5) were sorghum, holm oak, C. ladanifer and C. multiflorus for Flock 1, and meadow, holm oak, herbaceous sward, C. multiflorus and E. scoparia for Flock 6, all collected in the Morais ultrabasic complex. According to Kataeva et al. [37] and Baker et al. [38], Ni hyperaccumulation implies values higher than 1000 µg/g, so apparently no Ni hyperaccumulators were foraged by the animals. However, as meadows and herbaceous swards are composed of several species, a more refined technique for better understanding animal’s diet composition must be applied in the future in order to identify the existence or not of hyperaccumulators among this resource. On the other hand, some works have reported the existence of an endemic Ni hyperaccumulator, Alyssum pintodasilvae [8], but this plant was not among the three most consumed by the animals.

| Period | Plant | Ni (µg/g) | Flock |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn | Sorghum | 49.2 | 1 |

| Holm oak | 22.4 | 1 | |

| Meadow | 13.5 | 5 | |

| Meadow | 24.2 | 6 | |

| Holm oak | 19.9 | 6 | |

| Herbaceous sward | 10.3 | 6 | |

| Winter | Holm oak | 20.3 | 1 |

| Cistus ladanifer | 18.0 | 1 | |

| Meadow | 50.7 | 6 | |

| Holm oak | 13.6 | 6 | |

| Spring | Holm oak | 28.3 | 1 |

| Cytisus multiflorus | 19.0 | 1 | |

| Cytisus multiflorus | 25.0 | 6 | |

| Meadow | 13.3 | 6 | |

| Herbaceous sward | 10.8 | 6 | |

| Summer | Holm oak | 13.1 | 1 |

| Erica scoparia | 12.1 | 6 |

The high correlations between Ni and Cr, and Ni and Mg concentrations in soils were expected because it is known that ultrabasic soils are rich in these metals. The good correlations found between Mg and Cr, Mn and Cr, and Mn and Ni in soils are in line with those observed by Moraetis et al. [39] in serpentine soils in Greece where correlation coefficients of 0.68 and 0.53 were obtained for Cr-Ni and Mg-Cr, respectively. A lack of correlation between Cr concentrations in plants and soils was also reported by Fernández et al. [4] and Miranda et al. [16] for serpentine soils in the north-west of Spain.

The metal content of the grazing areas of Flocks 1 and 6, as well as of Flock 3, was quite well separated from the others. Three clusters were identified taking into account the metal concentrations of soils and/or plants of grazing areas. Flocks 1 and 6 form a homogeneous group related to high Ni, Mg and Cr soil concentrations associated with the Morais ultrabasic complex. Moreover, the highest metal concentrations in plants were also determined in those flocks. On the contrary, another cluster composed of Flocks 2, 4 and 5 had low Ni and Mg soil and plant concentrations, related to agricultural areas. The grazing area of Flock 3 formed another group because high Mn concentrations in soils and plants, as well as high Ca concentrations in plants, were determined occasionally. These results show that grazing circuits and the plants selected by the animals significantly influence the metal concentrations to which the animals are exposed.

CONCLUSION

The choice of grazing circuit by shepherds and the selection of the plants by animals influence the metal concentrations to which they are exposed. Those flocks that graze near the ultramafic complex (e.g. Flocks 1 and 6) are subjected to high Ni and Cr concentrations by soils and plants. In some areas, Ni concentrations in soils were above the recommended threshold for agricultural activity. Some plants grown in serpentine soils, such as sorghum, holm oak, C. multiflorus, C. ladanifer and E. scoparia, showed a Ni content above the threshold level for toxicity. Further studies are required to determine metal uptake by animals in order to establish policies for the management of flocks in such areas.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) and FEDER under Programme PT2020 for financial support to CIMO (UID/AGR/00690/2013).