All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Ryegrass Yield after Application of Solid-Liquid Pig Slurry and Biochar to an Agricultural Soil

Abstract

Background

The application of animal slurry to the soil improves its quality, as manure contains many nutrients for plants. However, this could negatively impact the environment.

Objective

This field study investigated the effects of the addition of biochar after the mechanical separation of Whole pig Slurry (WS) into Solid (SF) and Liquid Fractions (LF) on Greenhouse Gases (GHG) emissions (N2O, CO2, and CH4) and ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam. cv magnum) yield.

Methods

Biochar (1.0 kg m-2) was applied in plots alone or together with each of the three slurries (80 kg N ha-1) in a total of eight treatments with three replications, including just soil with and without biochar as controls. Soil properties, Greenhouse Gas (GHG) fluxes, and yield were measured during theautumn/winter growing season.

Results

The results showed that the addition of biochar to these three slurries significantly increased the soil pH and showed no impact on the other physicochemical properties. The GHG emissions were not significantly different between treatments with and without biochar. The N use efficiency increased significantly in SF > WS > LF, whereas no differences were observed among these three slurries with and without biochar.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that the addition of biochar combined with WS or SF/LF to sandy-loam soil appears to have no impact on GHG emissions and ryegrass yield during the autumn/winter season. Overall, this finding suggests that amounts higher than 1.0 kg m-2 of biochar combined with SF may need to be applied to soil to reduce GHG emissions and nitrate leaching and increase N use efficiency and crop yield.

1. INTRODUCTION

Globally, animal production has tended to rely on more intensive practices, resulting in increasing volumes of animal slurry (liquid manure). Scarlat et al. reported that, in the EU-28, around 1.3 billion tons of manure are produced annually from 89.5 million bovines, 147.8 million pigs, and 1.7 billion poultry [1]. Crop fertilization with animal slurries has a long tradition as a way of closing nutrient cycles on farms, emphasizing the concept of circular economy.

With the increase in the amount of animal slurry produced, environmental concerns have risen in recent years [2, 3]. Animal manure needs to be used efficiently, promoting agricultural soil fertility, protecting the environment (emissions into the atmosphere and leaching into the water system), and, finally, contributing to global health at the human-animal-ecosystem interface [4]. With the increase of slurry produced from animal farming, the monitoring and mitigation of Greenhouse Gases (GHG) and ammonia (NH3) emissions represent a major issue [5]. The two major GHGs emitted by the agriculture/livestock sector are methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). The European Union (EU) climate and energy framework has committed to reducing GHG emissions from animal waste and agriculture by 30% below 2005 levels in 2030, as stated in Regulation EU 2018/842.

The application of animal slurry to the soil improves its quality and reduces the use of mineral fertilizers and production costs, as it contains essential nutrients for crop growth [6]. Consequently, the use of slurries as a fertilizer is a sustainable agricultural practice that allows one to recycle nutrients that would otherwise be lost to the atmosphere and water. The mechanical separation of slurry is an adequate management technique of the manure that allows the separation of the Liquid Fraction (LF), rich in ammoniacal nitrogen (NH4+) and potassium (K), from the Solid Fraction (SF), rich in organic matter, P and relatively rich in nitrogen (N) [7].

Biochar, as a soil amendment, has shown potential for mitigating gaseous emissions, and its beneficial role in the improvement of soil quality is widely reported, enhancing crop yield and carbon (C) sequestration, particularly under adverse climatic conditions [8, 9, 10]. It is considered the easiest and most widely usable tool to increase soil C stocks [11-14]. The mechanisms through which biochar influences GHG emission are modification of soil aeration, water holding capacity, adsorption, pH, available nutrients, and activity of soil microbes and enzymes [15]. Despite the positive effects of biochar addition to soil, there is a gap in knowledge since previous studies are not conclusive about the effects of biochar in combination with both inorganic and organic fertilizers on climate conditions, soil type, nutrient availability, and use efficiency, crop productivity, mitigation of GHG emissions, and nutrient leaching [16-21].

The aim of this field study was to assess the effect of the addition of biochar after the mechanical separation of whole pig slurry on N2O, CO2, and CH4 emissions and ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam. cv magnum) yield from solid and liquid fractions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Location and Slurry Management

An experimental field was established from October 2019 to June 2020 at the Agrarian Higher School of Viseu (Viseu, Portugal; latitude: 40.641789º, longitude: -8.655840º). The long-term yearly mean air temperature in the region was 14.2 ºC, the monthly mean air minimum was 6.9 ºC in January, and the maximum was 21.4 ºC in July. The long-term average annual rainfall in the region was 1200 mm. The highest average monthly precipitation was recorded in December, with 204 mm. The average monthly temperatures and amounts of precipitation during this experiment were recorded by an automatic compact weather station (WS-GP1, Delta-T Devices Ltd, UK) and are presented in Table 1.

The soil used in this study was classified as Dystric Fluvisol [22], with a sandy-loam texture (44.2% coarse sand, 24.1% fine sand, 16.3% silt, and 15.4% clay). The physicochemical properties of the soil were determined by standard laboratory methods [19], with the following values: bulk density, 0.9 g cm-3, pH (H2O), 6.0, electrical conductivity, 0.02 mS cm-1, water holding capacity (WHC) at pF 2.0, 38.4% (w/w), total organic C, 15.60 g kg dry soil-1, and total N, 1.84 g kg dry soil-1.

| Month |

Soil Temperature (ºC) |

Air Temperature (ºC) |

Relative Humidity (%) |

Cumulative Rainfall (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| October 2019 | 18.7 ± 1.1 | 13.8 ± 1.3 | 83.2 ± 4.2 | 136.2 |

| November 2019 | 18.9 ± 1.4 | 10.1 ± 1.3 | 90.8 ± 2.1 | 260.6 |

| December 2019 | 17.3 ± 1.0 | 9.8 ± 0.9 | 83.0 ± 6.2 | 336.1 |

| January 2020 | 14.8 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 83.2 ± 5.6 | 121.7 |

| February 2020 | 17.2 ± 0.8 | 11.3 ± 0.9 | 78.4 ± 6.9 | 35.5 |

| March 2020 | 17.7 ± 0.8 | 11.4 ± 1.4 | 74.5 ± 5.8 | 124.2 |

| April 2020 | 17.7 ± 0.4 | 13.2 ± 0.9 | 85.0 ± 4.0 | 154.1 |

| May 2020 | 23.5 ± 1.2 | 18.8 ± 1.8 | 72.7 ± 5.0 | 49.7 |

| June 2020 | 23.6 ± 1.2 | 18.4 ± 1.6 | 73.1 ± 4.1 | 6.2 |

| Parameters |

Whole Slurry (WS) |

Solid Fraction (SF) |

Liquid Fraction (LF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion (% of raw slurry) | 100 ± 1 a | 20 ± 1 c | 80 ± 1 b |

| pH (H2O) | 7.8 ± 0.1 b | 7.9 ± 0.1 b | 8.6 ± 0.1 a |

| Dry matter (g kg-1) | 7.2 ± 2.7 b | 383.3 ± 5.3 a | 6.4 ± 0.9 b |

| Total C (g kg-1) | 33.7 ± 3.8 b | 53.5 ± 4.5 a | 17.4 ± 0.1 c |

| Total N (g kg-1) | 2.8 ± 0.1 b | 3.1±0.1 a | 2.6 ± 0.1 b |

| NH4+-N (g N kg-1) | 2.5 ± 0.1 a | 2.3 ± 0.1 a | 2.4 ± 0.1 a |

| NO3--N (mg N kg-1) | 7 ± 1 b | 26 ± 4 a | 8 ± 1 b |

| NH4+: total N ratio | 0.89 ± 0.01 a | 0.74 ± 0.01 b | 0.92 ± 0.01 a |

| C/N ratio | 12 ± 1 b | 18 ± 2 a | 7 ± 1 c |

| Application rate | - | - | - |

| kg C ha-1 | 969 ± 220 b | 1406 ± 298 a | 543 ± 6 c |

| kg N ha-1 | 80 ± 1 a | 80 ± 1 a | 80 ± 1 a |

| kg NH4+-N ha-1 | 71 ± 1 a | 60 ± 1 b | 74 ± 1 a |

The pig slurry used in this study came from a local farm. The whole slurry was subjected to mechanical separation by sieving through a 1.0 mm screen, generating a Solid Fraction (SF) and a Liquid Fraction (LF), with the following separation yields (w/w): 20% for SF and 80% for LF. The three slurries were subsampled in triplicate and analyzed by standard laboratory methods for the physicochemical properties detailed in Table 2 [6]. The soil texture was determined with the international pipette, soil bulk density by the Keen & Raczkowski method, pH (H2O) by potentiometry in a 1:2.5 soil: water ratio for soil and directly for slurry, water holding capacity by the gravimetric method, total C by the Dumas method, total N by the Kjeldahl method, and NH4+ and NO3− by spectrophotometry.

2.2. Experimental Details

The experiment was a randomized complete block design with three replicates and eight treatments. Field plots measuring 3.0 m x 2.0 m each were established and assigned treatments, totaling twenty-four plots. Three slurries (WS, SF, and LF) and control were considered in combination with and without biochar addition. Thus, the eight treatments considered were the following:

- Non-amended soil without and with biochar (Control and Biochar treatments),

- Application of whole slurry without and with biochar (WS and WS+Biochar treatments),

- Application of the solid fraction without and with biochar (SF and SF+Biochar treatments),

- Application of the liquid fraction without and with biochar (LF and LF+Biochar treatments).

After preparing the field soil by ploughing and discing, on the 20th of October 2019, WS, SF, and LF were manually applied to the soil of each designated plot at a rate of 80 kg N ha-1. Then, in each designated plot, biochar was applied manually at a rate of 1.0 kg m-2 [16, 19]. All soil plots were immediately scraped manually (20 mm depth) to incorporate the treatments and prevent NH3 volatilization from the slurries. Ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum Lam. cv magnum) was sown by hand the following day (21st October 2019) at a density of 35 kg ha-1 as used by local farmers. Ryegrass was rainfed, and no weed control was performed.

The commercial biochar (Ibero Massa Florestal, S.A., Portugal) was obtained from wood (agroforestry tree species) shavings (Ø = 2 mm) pyrolyzed in a muffle furnace at 900 °C. The main physicochemical properties of the biochar were determined by standard laboratory methods [19], with the following values: pH (H2O), 9.9; dry matter, 897.6 g kg-1; total C, 782.5 g kg-1; total N, 2.0 g kg-1; average particle size, 21 µm; 90% size of particles, > 37 µm; specific surface area, 22 m2 g-1; and pore volume, 1.1 mm3 g-1. Briefly, the biochar pH (H2O) was determined by potentiometry, dry matter by the gravimetric method, total C by the Dumas method, total N by the Kjeldahl method, particle size by the sieving method, specific surface area by the Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller method, and pore volume by mercury porosimetry.

2.3. Soil Mineral N and Crop Yield

Soil mineral N was determined in the 0-200 mm layer, 1, 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 days after the beginning of the experiment. A composite sample per plot was taken (six replicates), mixed, sieved (2 mm), and frozen (-18 ºC). A soil subsample was dried at 105 ºC to constant weight for gravimetric water content determination. Another subsample was used for pH determination. Then, the soil samples frozen were analyzed for NH4+ and NO3- concentrations by automated segmented flow spectrophotometry (San Plus, Skalar, Breda, The Netherlands) after extraction with 2 M KCl (1:5 w/v) and filtration (Whatman 42).

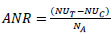

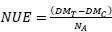

On the 7th of May 2020, the yield of the aboveground biomasses of ryegrass was obtained by cutting the crop to a height of 50 mm from 0.25 m2 in each plot and weighing it. The aliquot subsamples of the ryegrass were used to determine Dry Matter (DM) yields by drying to a constant mass at 65 ºC in a forced-draught oven. The N content in the samples was determined using the Kjeldahl method. Nitrogen uptake was determined by multiplying dry matter weight (aboveground biomass) by N content. The Apparent N Recovery (ANR) and N Use Efficiency (NUE) were calculated using the Eqs. (1 and 2), respectively, as mentioned below [7, 23]:

|

(1) |

where, ANR isthe apparent N recovery in each amended treatment (g g-1), NUT is the N in the DM yield obtained with the amendment treatment, NUC isthe N in the DM yield obtained with the Control treatment, and NA is referred to the N provided by the slurries.

|

(2) |

where, NUE isthe N use efficiency in each amended treatment (g DM g-1 N), DMT is the DM yield obtained with the amendment treatment, DMC is the DM yield obtained with the Control treatment, and NA is referred to the N provided by the slurries.

2.4. Gas Flux Measurements

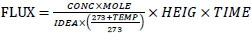

Fluxes of N2O, CO2, and CH4 were measured using the closed chamber technique and following the procedure described in Fangueiro et al. [6]. Gas measurements were carried out 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, and 9 days after the experiment’s beginning, twice a week until day 30, once a week until day 60, and twice a month at the end of the experiment. To evaluate the GHG gas fluxes from each treatment, a circular chamber of polyvinyl chloride (Ø = 200 mm, h = 110 mm), equipped with a septum to sample the interior atmosphere, was inserted into the soil (depth = 30 mm). The chambers were kept at fixed locations throughout the sampling dates. After the chamber was closed, a first gas sample (25 mL) was taken (t = 0.0 h) using a plastic syringe and flushed through gas vials (20 mL), then a second (t = 0.5 h) and a third (t = 1.0 h) gas sample was taken from the headspace of the chamber and stored in vials [6]. The concentrations of the gas samples stored in vials were measured by gas chromatography using a GC-2014 (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for CO2 and an electron capture 63Ni detector (ECD) for N2O. The GC-2014 accuracy was 1 ppm to 1% for CO2 and 50 ppb to 100 ppm for N2O. The N2O, CO2, and CH4 fluxes were determined using Eq. (3), given as follows [6]:

|

(3) |

where, FLUX is the N2O, CH4, or CO2 flux on each sampling date (g N or C m-2 day-1), CONC is the gas concentration (m3 m-3), MOLE is the gas molecular weight (44 g mol-1 for N2O or CO2 and 16 g mol-1 for CH4), IDEA is the volume of an ideal gas (0.0224 m3 mol-1), TEMP is the temperature during the sampling period (ºC), HEIG is the height of the chamber (0.080 m), and TIME isthe time corrected per day.

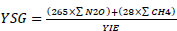

To calculate cumulative gas emissions, the flux between two sampling occasions was averaged and then multiplied by the time interval between the measurements. The conversion factors of 265 for N2O and 28 for CH4 were used to express the Global Warming Potential (GWP) [24] as CO2 -equivalents, using Eq. (4), given as follow:

|

(4) |

where, YSG is the net GWP per unit of ryegrass yield (g CO2-eq g-1), ΣN2O and ΣCH4 are the accumulated amounts of N2O and CH4 released during ryegrass cropping (g CO2-eq m-2), and YIE is the ryegrass yield (g m-2).

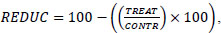

The N2O, CO2, CH4, and GWP losses from amended treatments areexpressed as reduction efficiencies [24] using Eq. (5), as follows:

|

(5) |

where, REDUC isthe reduction efficiency from each amended treatment relative to the Control treatment (%), TREAT isthe mean value of the individual/cumulative gas loss from each amended treatment, and CONTR isthe mean value of the individual/cumulative gas loss from the Control treatment.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Analysis of variance was conductedusing the statistical software package STATISTIX 10 (Analytical Software, Tallahassee, FL, USA) to assess the effect of slurries, biochar, and slurries × biochar interaction. The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was used to determine the normality of the analyzed traits' distribution [25, 26]. The collected data was analyxed per day, and for the whole experiment, a randomized complete block design was considered using two factors: slurries and biochar. Tukey comparisons of means (p < 0.05) were carried out for the factors and their interactions [27].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Soil Properties

The concentrations of NH4+ in the soil of each treatment are presented in Table 3 and were lower than 11 mg NH4+-N kg-1 of dry soil in the control and biochar treatments during the 195 days of the experiment. In the first 6 days of the study, NH4+ concentrations increased significantly (p < 0.05) in treatments that received slurries (WS, SF and LF), without and with biochar (WS+Biochar, SF+Biochar and LF+Biochar), when compared to treatments without slurries (control and biochar), with concentrations that ranged from 27 to 75 mg NH4+-N kg-1 of dry soil being observed (Table 3). From day 14 until the end of the experiment, the NH4+ concentrations did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) between treatments without and with slurries, and they declined to background levels (9 to 3 mg NH4+-N kg-1 of dry soil) by the nitrification process (Table 3). The NH4+ concentrations in treatments with and without biochar did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) during the experiment, although numerically higher values were observed in some measurements of treatments with biochar (Table 3).

The initial concentrations of NO3- in the control and biochar treatments were low and remained constant until the end of the experiment (Table 4). Compared to treatments without slurries, an increase in NO3- concentrations was observed in treatments that received slurries with and without biochar, with a peak observed on day 6 (15 to 22 mg NO3--N kg-1 of dry soil) followed by a decrease to background levels by the end of the experiment (Table 4). In most measurement days, no significant differences (p > 0.05) of NO3- concentrations between all treatments with and without biochar were observed (Table 4).

| - | Days of Experiment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 14 | Day 22 | Day 37 | Day 76 | Day 120 | Day 195 |

| - | (mg NH4+-N kg-1 dry soil) | ||||||||

| Control | 4 ± 2 e | 9 ± 1 b | 4 ± 1 c | 6 ± 3 a | 7 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a | 5 ± 1 c | 9 ± 2 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| Biochar | 11 ± 3 de | 10 ± 1 b | 4 ± 1 c | 6 ± 2 a | 8 ± 1 a | 4 ± 1 a | 9 ± 1 abc | 8 ± 2 a | 2 ± 1 a |

| WS | 66 ± 20 ab | 49 ± 14 a | 33 ± 1 b | 9 ± 6 a | 16 ± 3 a | 6 ± 1 a | 9 ± 2 abc | 6 ± 1 a | 2 ± 1 a |

| WS+Biochar | 69 ± 26 a | 58 ± 2 a | 75 ± 18 a | 3 ± 2 a | 20 ± 9 a | 6 ± 1 a | 9 ± 1 abc | 7 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| SF | 27 ± 9 cd | 43 ± 12 a | 35 ± 6 b | 7 ± 5 a | 12 ± 4 a | 5 ± 1a | 11 ± 1 a | 6 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| SF+Biochar | 18 ± 4 cd | 46 ± 3 a | 35 ± 5 b | 2 ± 1 a | 10 ± 1 a | 6 ± 1 a | 9 ± 1 abc | 7 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| LF | 56 ± 17 bc | 52 ± 11 a | 31 ± 13 b | 3 ± 2 a | 17 ± 4 a | 5 ± 1 a | 5 ± 1 bc | 7 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| LF+Biochar | 48 ± 7 bcd | 50 ± 5 a | 38 ± 11 b | 7 ± 6 a | 12 ± 1 a | 4 ± 1 a | 10 ± 3 ab | 7 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a |

| p slurries (A) | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| - | Days of Experiment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 14 | Day 22 | Day 37 | Day 76 | Day 120 | Day 195 |

| - | (mg NO3--N kg-1 dry soil) | ||||||||

| Control | 2 ± 1 b | 9 ± 4 ab | 6 ± 3 b | 20 ± 6 a | 4 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab |

| Biochar | 5 ± 2 ab | 6 ± 1 b | 9 ± 5 ab | 7 ± 1 ab | 2 ± 1 b | 3 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b |

| WS | 7 ± 2 a | 9 ± 1 ab | 17 ± 2 ab | 7 ± 5 ab | 27 ± 8 a | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 3 ± 2 a | 1 ± 1 ab |

| WS+Biochar | 6 ± 2 ab | 8 ± 1 ab | 15 ± 2 ab | 4 ± 2 b | 12 ± 9 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab |

| SF | 5 ± 2 ab | 15 ± 3 a | 19 ± 3 ab | 10 ± 2 ab | 3 ± 1 b | 3 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a |

| SF+Biochar | 4 ± 1 ab | 14 ± 2 a | 21 ± 4 a | 8 ± 4 ab | 5 ± 2 b | 3 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 ab |

| LF | 4 ± 1 ab | 13 ± 1 a | 18 ± 6 ab | 9 ± 3 ab | 11 ± 5 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b |

| LF+Biochar | 4 ± 1 ab | 14 ± 2 a | 22 ± 4 a | 10 ± 6 ab | 20 ± 10 ab | 4 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a |

| p slurries (A) | ns | * | * | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| - | Days of Experiment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 14 | Day 22 | Day 37 | Day 76 | Day 120 | Day 195 |

| Control | 6.6 ± 0.1 b | 6.1 ± 0.1 d | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 6.4 ± 0.1 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 b | 6.5 ± 0.1 ab | 5.9 ± 0.2 b |

| Biochar | 6.8 ± 0.1 b | 6.6 ± 0.1 abc | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 a | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 a |

| WS | 6.5 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 cd | 6.6 ± 0.1 ab | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 a | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 b | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 5.7 ± 0.2 b |

| WS+Biochar | 7.2 ± 0.3 a | 6.8 ± 0.1 ab | 6.9 ± 0.2 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 a | 6.8 ± 0.1 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 5.7 ± 0.1 b |

| SF | 6.5 ± 0.1 b | 6.4 ± 0.2 bc | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 6.7 ± 0.2 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 a | 6.8 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 5.9 ± 0.1 ab |

| SF+Biochar | 6.8 ± 0.1 ab | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.5 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 a | 7.0 ± 0.2 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 5.8 ± 0.3 b |

| LF | 6.7 ± 0.1 ab | 6.6 ± 0.1 abc | 6.5 ± 0.1 b | 6.6 ± 0.2 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 a | 7.0 ± 0.2 a | 6.6 ± 0.1 b | 6.3 ± 0.1 b | 6.1 ± 0.1 ab |

| LF+Biochar | 7.2 ± 0.3 a | 6.5 ± 0.1 bc | 6.8 ± 0.2 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 a | 6.7 ± 0.1 a | 6.9 ± 0.1 a | 6.8 ± 0.1 a | 6.4 ± 0.1 b | 6.0 ± 0.2 ab |

| p slurries (A) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ** | ** | ** | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| - | Days of Experiment | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 2-3 | Day 4-7 | Day 8-18 | Day 19-42 | Day 43-74 | Day 44-75 | Day 76-121 | Day 122-138 | Day 139-195 | ∑0-195 | ∑0-195 |

| - | (µg N2O-N m-2 day-1) | (kg N2O-N ha-1) | (% N applied) | |||||||||

| Control | 515 ± 172 a | 97 ± 31 b | 194 ± 34 a | 319 ± 146 d | 59 ± 17 b | 108 ± 93 a | 38 ± 33 a | 6 ± 5 b | 97 ± 43 a | 46 ± 21 b | 0.6 ± 0.1 c | - |

| Biochar | 630 ± 51 a | 86 ± 29 b | 123 ± 73 a | 427 ± 21 d | 57 ± 17 b | 51 ± 33 a | 1 ± 1 a | 51 ± 10 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 179 ± 9 a | 0.5 ± 0.1 c | - |

| WS | 1285 ± 667 a | 1468 ± 676 a | 489 ± 32 a | 2867 ± 672 bcd | 807 ± 268 a | 1 ± 1 a | 19 ± 10 a | 60 ± 23 ab | 53 ± 46 a | 84 ± 39 b | 2.5 ± 0.5 ab | 3.1 ± 0.6 ab |

| WS+Biochar | 1269 ± 228 a | 866 ± 359 ab | 739 ± 199 a | 5436 ± 2458 ab | 285 ± 153 b | 32 ± 14 a | 22 ± 14 a | 101 ± 31 a | 34 ± 30 a | 63 ± 19 b | 2.7 ± 0.9 ab | 3.4 ± 1.2 ab |

| SF | 985 ± 231 a | 555 ± 241 ab | 578 ± 299 a | 2015 ± 713 cd | 178 ± 93 b | 12 ± 9 a | 25 ± 21 a | 36 ± 23 b | 69 ± 42 a | 32 ± 23 b | 1.3 ± 0.4 bc | 1.6 ± 0.5 b |

| SF+Biochar | 752 ± 70 a | 258 ± 125 ab | 189 ± 10 a | 2614 ± 350 bcd | 56 ± 11 b | 16 ± 14 a | 13 ± 11 a | 4 ± 4 b | 17 ± 4 a | 1 ± 1 b | 1.1 ± 0.1 bc | 1.4 ± 0.2 b |

| LF | 1319 ± 282 a | 878 ± 321 ab | 680 ± 255 a | 3798 ± 593 bc | 130 ± 32 b | 293 ± 253 a | 9 ± 8 a | 10 ± 9 b | 27 ± 24 a | 56 ± 37 b | 1.9 ± 0.2 abc | 2.3 ± 0.2 ab |

| LF+Biochar | 1150 ± 247 a | 1213 ± 420 ab | 406 ± 206 a | 7911 ± 963 a | 419 ± 189 ab | 4 ± 3 a | 1 ± 1 a | 4 ± 4 b | 87 ± 41 a | 21 ± 9 b | 3.5 ± 0.5 a | 4.3 ± 0.6 a |

| p slurries (A) | ns | * | ns | *** | * | ns | ns | ** | ns | * | *** | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns | ns |

The pH of the soil in the control treatment varied slowly (6.6 to 5.9) from the beginning to the end of the experiment (Table 5). Compared to the control treatment, soil pH increased numerically (p > 0.05) in all other treatments during the first 6 days, followed by a decrease in control levels at the end of the experiment (Table 5). Furthermore, soil pH increased in all treatments that received biochar, compared to the same treatments without biochar, but no significant variation (p > 0.05) was observed (Table 5).

3.2. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

In the first 42 days of the experiment, the daily N2O fluxes increased in all treatments relative to control and biochar treatments, followed by a similar pattern to these treatments until the end of the experiment (Table 6). The first peak was observed in the first 3 days of the experiment (260-1470 μg N2O-N m-2 day-1), and the second peak reached in days 8-18 (2015-7911 μg N2O-N m-2 day-1) (Table 6). Then, the N2O fluxes decreased in all treatments until the end of the experiment (Table 6). In comparison to the WS and LF treatments, the N2O fluxes from the SF treatments were reduced by ca. 26% during the first 42 days of the experiment (Table 6). In most measurement days, no significant differences (p > 0.05) in N2O fluxes between all treatments without and with biochar were observed, although numerically lower fluxes in SF treatment without biochar were observed (Table 6). Compared to the control treatment, the cumulative N2O emissions increased, but not significantly (p > 0.05), in treatments that received slurries by 393% for WS and 187% for SF/LF (Table 6). Also, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in cumulative N2O emissions, expressed as a percentage of N applied, from treatments that received slurries, although higher losses in WS treatment (3.1% for WS against 1.6% for SF) were observed (Table 6). However, no significant differences (p > 0.05) in cumulative N2O emissions between all treatments, expressed as absolute values or as a percentage of N applied, were observed (Table 6).

The CO2 daily fluxes increased in all treatments relative to control and biochar treatments, followed by a reduction until the end of the measurements (Table 7). The first peak was observed on days 8-18 (5-11 g CO2 m-2 day-1) of the experiment, and the second peak was detected on days 122-138 (4-11 g CO2 m-2 day-1) (Table 7). Compared to the WS and LF treatments, the CO2 fluxes from the SF treatments reached an increase of ca. 50% in most measurements (Table 7). No significant differences (p > 0.05) in CO2 fluxes among all treatments without and with biochar were observed (Table 7). The cumulative CO2 emission of SF treatment was significantly higher (p < 0.05) by 100% than all treatments without biochar (Table 7). The cumulative CO2 emissions did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) among all treatments with and without biochar, although numerically higher values, around 60%, were observed for WS+Biochar and LF+Biochar treatments (Table 7).

Measurable CH4 fluxes were observed from the beginning until the end of the experiment, with values that varied from -1 to 11 mg CH4 m-2 day-1 (Table 8). Compared to control and biochar treatments, the peak was observed on days 8-18 (9–11 g CH4 m-2 day-1) in WS and WS+Biochar treatments, while all other treatments peaked (7-10-g CH4 m-2 day-1) on days 43-74 (Table 8). In other measured dates, the daily fluxes of CH4 did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) among treatments with and without biochar and followed a similar trend in the remaining measurements (Table 8). The cumulative CH4 emissions in treatments that received slurries were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in control, with increases between 135 and 160% (Table 8). No significant difference (p > 0.05) in cumulative CH4 emissions between treatments with and without biochar was observed, although a numerical reduction of 37% was observed in the SF treatment compared to SF+Biochar (Table 8).

The GWP, expressed as CO2-equivalents, in the SF treatment was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in control and WS/LF treatments, with increases between 135 and 160% (Table 9). The cumulative GWP emissions were not significantly different (p > 0.05) between treatments with and without biochar, although a numerical reduction of 25% was observed in the SF treatment compared to SF+Biochar (Table 9). The yield-scaled GWP was not significantly different (p > 0.05) between the control and treatments that received slurries, although it was numerically lower (-34 to -51%) in the WS/LF treatments (Table 9). The yield-scaled GWP emissions were not significantly different (p > 0.05) between treatments with and without biochar, although a numerical reduction of 21% was observed in the SF+Biochar treatment compared to SF (Table 9).

| - | Days of Experiment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 2-3 | Day 4-7 | Day 8-18 | Day 19-42 | Day 43-74 | Day 44-75 | Day 76-121 | Day 122-138 | Day 139-195 | ∑0-195 |

| - | (g CO2 m-2 day-1) | (ton CO2 ha-1) | |||||||||

| Control | 2 ± 1 bc | 2 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 abc | 5 ± 1 c | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 6 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a | 18.9 ± 0.7 b |

| Biochar | 1 ± 1 c | 2 ± 1 b | 2 ± 1 c | 5 ± 1 c | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 5 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a | 18.7 ± 4.1 b |

| WS | 3 ± 1 ab | 5 ± 2 a | 3 ± 1 ab | 5 ± 1 c | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 4 ± 2 a | 1 ± 1 a | 15.8 ± 4.5 b |

| WS+Biochar | 4 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 abc | 6 ± 1 c | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 2 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 ab | 8 ± 3 a | 1 ± 1 a | 25.4 ± 3.3 ab |

| SF | 2 ± 1 abc | 3 ± 2 ab | 4 ± 1 a | 10 ± 2 ab | 4 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 5 ± 2 a | 11 ± 3 a | 3 ± 1 a | 38.8 ± 3.5 a |

| SF+Biochar | 2 ± 1 bc | 3 ± 1 ab | 2 ± 1 bc | 11 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 10 ± 1 a | 3 ± 2 a | 28.9 ± 2.6 ab |

| LF | 2 ± 1 abc | 3 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 abc | 6 ± 1 c | 2 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 b | 2 ± 1 ab | 5 ± 2 a | 2 ± 1 a | 19.5 ± 5.9 b |

| LF+Biochar | 2 ± 1 bc | 3 ± 1 ab | 2 ± 1 c | 7 ± 1 bc | 3 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 3 ± 2 a | 1 ± 1 b | 10 ± 3 a | 4 ± 2 a | 31.5 ± 9.6 ab |

| p slurries (A) | * | ns | ns | ** | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| - | Days of Experiment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Day 1 | Day 2-3 | Day 4-7 | Day 8-18 | Day 19-42 | Day 43-74 | Day 44-75 | Day 76-121 | Day 122-138 | Day 139-195 | ∑0-195 |

| - | (mg CH4 m-2 day-1) | (kg CH4 ha-1) | |||||||||

| Control | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 2 ± 4 a | 1 ± 1 a | -1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 3.0 ± 1.8 a |

| Biochar | -1 ± 1 b | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 8 ± 2 a | 2 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 5 ± 1 a | 3 ± 1 a | 5.2 ± 1.5 a |

| WS | 1 ± 1 ab | 3 ± 1 a | 2 ± 1 a | 11 ± 9 a | 2 ± 1 a | 2 ± 5 a | -1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 b | 7.8 ± 6.8 a |

| WS+Biochar | 8 ± 7 a | 3 ± 1 a | 5 ± 1 a | 9 ± 5 a | 2 ± 1 a | 7 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 13.8 ± 3.3 a |

| SF | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 7 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 7.1 ± 1.6 a |

| SF+Biochar | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 8 ± 2 a | 1 ± 1 a | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 4.4 ± 0.5 a |

| LF | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | 10 ± 1 a | -1 ± 1 a | -1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 7.4 ± 2.3 a |

| LF+Biochar | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 ab | 1 ± 1 a | 5 ± 4 a | 1 ± 1 a | 8 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 a | -1 ± 1 b | 1 ± 1 a | 1 ± 1 ab | 7.2 ± 0.8 a |

| p slurries (A) | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| - | GWP | Yield | Yield | Apparent N Recovery | N Use Efficiency | Yield-scaled GWP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | ton N ha-1 | ton DM ha-1 | kg N ha-1 | % N Applied | kg DM kg N-1 | ton CO2-eq. ton-1 |

| Control | 19.2 ± 0.8 b | 2.6 ± 0.1 e | 25.9 ± 1.2 e | - | - | 7.5 ± 0.2 ab |

| Biochar | 19.0 ± 4.1 b | 2.8 ± 0.1 e | 35.7 ± 0.5 d | - | - | 6.8 ± 1.5 ab |

| WS | 16.6 ± 4.4 b | 4.6 ± 0.2 b | 79.7 ± 3.2 b | 67.2 ± 4.0 a | 26.0 ± 2.7 b | 3.7 ± 1.1 b |

| WS+Biochar | 26.5 ± 3.6 ab | 4.4 ± 0.1 bc | 86.7 ± 2.5 a | 75.9 ± 3.1 a | 23.3 ± 1.1 bc | 5.9 ± 0.7 ab |

| SF | 39.3 ± 3.6 a | 5.9 ± 0.2 a | 86.4 ± 2.3 a | 75.6 ± 2.8 a | 41.8 ± 2.2 a | 6.7 ± 0.8 ab |

| SF+Biochar | 29.3 ± 2.6 ab | 5.6 ± 0.1 a | 84.2 ± 2.4 ab | 72.9 ± 3.0 a | 37.3 ± 1.8 a | 5.3 ± 0.6 ab |

| LF | 20.2 ± 5.9 b | 4.1 ± 0.1 cd | 65.3 ± 0.9 c | 49.2 ± 1.1 b | 19.2 ± 0.8 cd | 4.9 ± 1.4 ab |

| LF+Biochar | 32.3 ± 9.6 ab | 3.8 ± 0.1 d | 60.8 ± 0.3 c | 43.6 ± 0.4 b | 15.3 ± 0.3 d | 8.5 ± 2.5 a |

| p slurries (A) | ns | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns |

| p biochar (B) | ns | ns | ns | ns | * | ns |

| A × B | ns | ns | ** | ns | ns | ns |

3.3. Crop Productivity

The DM yield, expressed in DM per ha, in treatments that received slurries was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in control, with increases between 60 and 130% (Table 9). The DM yield, expressed in DM per ha, was not significantly different (p > 0.05) between treatments with and without biochar (Table 9). The DM yield, expressed in N per ha, was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in treatments that received slurries than in Control, with increases in the following order: SF > WS > LF (Table 9). The DM yield, expressed in N per ha, from the Biochar treatment was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in Control (more than 38%), while the DM yield from WS+Biochar was higher (p > 0.05) than that of the WS treatment (Table 9). The apparent N recovery in treatments receiving WS/SF was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than in the LF treatment (> 67.2% of N applied for WS/SF against 49.2% of N applied for LF) (Table 9). No significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in apparent N recovery between treatments with and without biochar (Table 9). The N use efficiency increased significantly (p < 0.05) in treatments that received slurries in the following order: SF > WS > LF, with more than 41 kg DM kg-1 N for SF and from 19 to 26 kg DM kg-1 N for WS/LF (Table 9). The N use efficiency was not significantly different (p > 0.05) between treatments with and without biochar, although a numerical reduction of 10 to 20% in biochar treatments was observed (Table 9).

4. DISCUSSION

The application of slurries (WS, SF, and LF) to amended treatments increased the NH4+ concentration in the first two weeks due to the high NH4+: total N ratio (0.74 to 0.92) (Table 2). Although the SF had significantly higher contents of DM and total C than the WS/LF, immobilization seems to have had no impact on the reduction of NH4+ availability in this slurry fraction. The lack of differences in NH4+ concentrations in treatments with and without biochar (Table 3) was consistent with previous studies [14, 19], which reported that the application of biochar into the soil led to NH4+ ion adsorption, as biochar can act as a cation exchange medium and has a high capacity for N sorption. As can be observed in Table 2, the characteristics of the three slurries were distinct, and the application rate was based on total N (80 kg N ha-1). Hence, the total C applied in SF was significantly higher than in WS/LF, whereas NH4+ applied was significantly lower in SF. Previous studies [28, 29] observed that the high C/N ratio of the SF can induce a higher immobilization of N by the soil microbial biomass. The lack of differences in NO3- concentrations between SF and WS/LF without and with biochar could be related to the NO3- leaching by the high rainfall that occurred between October and February (855 mm) and represented 70% of the cumulative rainfall during the experiment (Table 1). However, the addition of manure with biochar had the potential to decrease the N leaching losses by 11% when compared to manure only [30]. Saarnio et al. [31] reported that the application of biochar at rates of 1.0 to 3.0 kg m-2 does not contribute to the reduction of GHG emissions nor to the reduction of N or P leaching from peat soil in the short term, suggesting that larger quantities are needed. The application of slurries (WS, SL, and LF) led to the addition of significant amounts of N in organic and mineral forms to the soil. Some NH4+ can be nitrified, releasing H+ that decreases soil pH [5], which is different from when the plant exists in the system [32, 33]. Similar studies have reported that the addition of biochar to soil increases overall pH because pyrolysis leads to the accumulation of alkaline substances on the biochar surface, which increases the soil pH [9, 11, 18, 19, 34-36].

The N2O emissions came from the nitrification and denitrification processes, depending on the soil water content. Denitrification is the main source of N2O fluxes from agricultural soil amended with slurries [37]. The increase in N2O emissions from the treatments that received slurries in relation to the control is due to the addition of high concentrations of NH4+, organic N, and readily available organic C, increasing the processes of nitrification and denitrification (Table 2) [38]. The availability of organic compounds as a C source in WS could be the reason for higher N2O emissions from this treatment relative to SF/LF. Previous studies have reported that biochar application to soils could decrease, increase, or have no effect on N2O, CO2, and CH4 emissions, depending on soil texture, biochar type, and their co-application with organic or inorganic fertilizers [16-19, 39, 40]. The following mechanisms are involved after biochar application into the soil: (i) reduction of NO3- to N2, N2O/N2 ratio, and N2O losses by the increase of soil pH [41]; (ii) reduction of denitrification and N2O losses by the improvement of soil aeration [42]; and (iii) reduction of inorganic N availability and N2O losses due N immobilization. The results of the present study put forward that to reach a significant N2O reduction in soil with a sandy-loam texture, higher amounts (> 1.0 kg m-2) of biochar are needed. In acidic or coarse-textured soils, previous studies [43, 44] reported an increase in crop yields with increasing biochar application rates (0.5-15.0 kg m−2), which may be attributed to the liming effect and enhanced soil water storage, potentially improving nutrient availability. . Although results from different soil types cannot be directly extrapolated, the impact on soil N losses after biochar application depends on the physicochemical properties and modifications in the abundance and diversity of the microbial community [31, 45].

Carbon dioxide emissions are due to soil respiration, depending on the soil texture, water content, temperature, aeration, microbial activity and C mineralization, crop residues, and organic and inorganic fertilizer use [16, 29, 46, 47]. The application of slurries increases soil microbial activity and CO2 fluxes due to the mineralization of organic matter, whereas rainfall reduces the availability of organic fertilizer [29]. In this study, the CO2 emissions from the SF treatment were higher relative to WS/LF, which was consistent with the significantly higher amount of total C added by SF (53.5 g kg-1 in SF against less than 33.7 g kg-1 in WS/LF) (Table 2). Previous studies are not unanimous about the influence of biochar in CO2 released from the soil depending on soil properties, temperature, or fertilizer type [16, 38, 48]. In this study, biochar increased, but not significantly, the cumulative CO2 emissions from WS/LF relative to SF. This may be related to increased rates of C mineralization in these treatments, either due to mineralization of the labile C added with the biochar or through increased mineralization of the soil organic matter [38].

Methane emissions are due to soil aeration, and positive or negative fluxes are a result of CH4 production by anaerobic methanogenic organisms and CH4 consumption by aerobic methanotrophic organisms [49, 50]. Previous studies [29, 51] reported that the slurry application into soil enhances CH4 emissions for a few days due to the release of dissolved CH4 during storage. Additionally, the rainfall events enhance the net CH4 emission from methanogenesis in soil. In this study, the rainfall events should have enhanced the methanogenic activity in the soil, allowing it to act as a CH4 source (Tables 1 and 8). Applying biochar to soil increases CH4 absorption because it improves CH4 oxidation through soil aeration, decreasing this loss over time [15, 52, 53]. However, in the present study, the addition of biochar to soil did not reduce the CH4 emissions from slurries, although a numerical reduction in SF was observed. This decrease in CH4 emissions in SF could be related to the reduction of anaerobic conditions by biochar addition to the soil [54]. In any case, the results of the present study are in line with previous studies [15-17, 38], which reported that animal manure and biochar generally have little effect on CH4 flux from soils. The results of the present study are in line with those of other studies, in which biochar had no impact on yield-scaled GWP without the application of an N fertilizer (Table 9) [16, 19].

Slurry separation makes it feasible to concentrate DM, organic N, and P in the SF, which can then be exported from the farm to regions with nutrient shortfalls or directed toward other portions of the farm [7]. The SF is very rich in recalcitrant C fractions such as lignin, hemicellulose, and lignocellulose, whereas the LF is rich in labile C fractions and contains the largest fraction of the NH4+ of the WS, being stored in the farm until used as an organic fertilizer [55]. The amount of slurry applied in each treatment was based on total N, and consequently, the amount of NH4+ applied varied between treatments, being lower in SF compared to WS/LF (Table 2). The slurry was applied in October, and 70% of the rain recorded during the experiment fell until January (Tables 1 and 2), increasing the leaching of NO3- during this period, except in SF, due to immobilization, as it should be the dominant process given the high C/N ratio and low water-soluble C in relation to total C [29]. The higher DM yield in SF compared to that of WS/LF may also be related to N immobilization, which can reduce NO3- leaching between October and May. The use of biochar can improve soil properties, which results in greater crop growth and productivity under normal conditions, as well as in soils that present abiotic stresses due to the presence of heavy metals, salt, or organic contaminants [53, 56]. In the present study, the addition of biochar to slurries had no effect on N use efficiency, concurring with previous studies, which reported that, in temperate climates, soils are often in good condition, characterized by a perfectly adjusted soil pH and high nutrient availability (Table 9) [17, 20]. To validate and expand the results observed in this short period, it is essential to conduct extensive, long-term investigations in future research to understand discrepancies in emissions and discover the most effective practices (rate, depth, and frequency) for using biochar in agricultural soils [57].

CONCLUSION

Data from this study indicated that the mechanical separation of the WS generates an LF and an SF with two distinct compositions, with significantly higher contents of DM and total C in SF. The addition of biochar to these three slurries significantly increased the soil pH and seemed to have no impact on the other physicochemical characteristics of the soil. The cumulative N2O and CH4 emissions did not differ significantly between the three slurries, whereas CO2 emissions and GWP were significantly higher in SF treatment. The emissions of N2O, CO2, CH4, and GWP were not significantly different between treatments with and without biochar. The DM yield, expressed in N per ha, increased significantly in SF > WS > LF, while the addition of biochar significantly increased DM yield in WS. The apparent N recovery in WS/SF was significantly higher than in LF, but these three slurries, with and without biochar, did not differ significantly in apparent N recovery. N use efficiency increased significantly in SF > WS > LF, whereas no differences were observed among these three slurries with and without biochar.

Thus, it can be concluded that the addition of biochar combined with WS or SF/LF to sandy-loam soil appears to have no impact on GHG emissions and ryegrass yield during the autumn/winter season. Overall, these findings suggest that amounts higher than 1.0 kg m-2 of biochar, combined with SF, may need to be applied to soils to reduce GHG emissions and nitrate leaching, and to increase N use efficiency and crop yield. Future studies are recommended to explore different soil types, crop species, andenvironmental conditions to validate these findings.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

FUNDING

This work was supported by National Funds from FCT - Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the projects UIDB/00681/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/00681/2020), UIDB/04033/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04033/2020), UIDB/50006/2020 and UIDP/50006/2020 (Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia), and the projects WASTECLEAN PROJ/IPV/ID&I/019 (Polytechnic Institute of Viseu), WASTE2VALUE PDR2020-1.0.1-FEADER-032314 (Ministério da Agricultura) and FEEDVALUE PRR-C05-i03-I-000242 (European Union).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.